ATAD 3: what are the consequences of being a shell?

Examining these reveals how the Unshell Directive could in practice result in layers of double taxation in previously tax efficient structures. While this may deter international groups from using EU companies as intermediate holding companies and encourage existing structures to be reorganised, the effectiveness of the Unshell Directive may be in doubt, particularly where third countries are involved.

ATAD 3 (or the Unshell Directive), the European Commission’s Directive designed to tackle the use of EU based shell entities (an EU Shell) that do not meet a minimum substance threshold, is intended to come into force from 1 January 2024. Many international corporate groups that use European holding companies will therefore be grappling with whether any of their companies are EU shells, and if so, what to do about it.

Such groups might consider removing problematic holding companies, using different jurisdictions, or taking steps to bolster substance in particular jurisdictions in order to stay above the new minimum threshold. Before doing so, groups should examine their structures not just in light of the minimum substance requirements laid out by the Unshell Directive, but also taking into account the potential tax implications of the Directive should it have effect.

This article looks at the intended tax consequences of the Unshell Directive, as set out in its preamble, in the context of payments of dividends and interest and asks whether, and how, implementing legislation will be able to achieve its aims.

What are the tax consequences of being a shell?

Where an entity meets the conditions to be treated as a shell, and is unable to meet the minimum substance requirements or satisfy the tax motive exemption, it will be classified as a shell entity and subject to the consequences set out in articles 11 and 12 of the Directive.

The stated aims of the Directive in these circumstances are to neutralise the tax effects of introducing the shell entity by "disallowing any tax advantages which have been obtained, or could be obtained" through the shell. In broad terms, this is achieved by:

- requiring EU member states (other than the state of residence of the shell entity) to deny the shell entity the tax benefits and reliefs provided by the Parent-Subsidiary Directive (PSD), the Interest and Royalties Directive (IRD) (together, the EU Directives), and bilateral tax treaties;

- requiring an EU member state in which the shell entity is resident to refuse the shell entity a tax residence certificate for the purpose of claiming such reliefs or to issue a certificate which states that the shell entity is not entitled to such reliefs; and

- imposing obligations on EU member states in which the shareholders of the shell entity are resident to tax the income of the shell entity as if it had accrued directly to the shareholder.

Illustrative examples in practice

The preamble to the Directive includes four scenarios, each of which considers the tax treatment of a payment made by a paying entity to an EU Shell (payment 1) and an onward payment by EU Shell to a shareholder (payment 2) for cases where the payer and the shareholder are resident in an EU member state or a third country. We consider each of these scenarios below and compare:

- the tax advantage the Unshell Directive seeks to deny;

- how the Directive is intended to apply, according to the scenarios described in the preamble; and

- the practical issues with the tax consequences the preamble envisages will apply to payment flows of interest and dividends involving EU and third country jurisdictions.

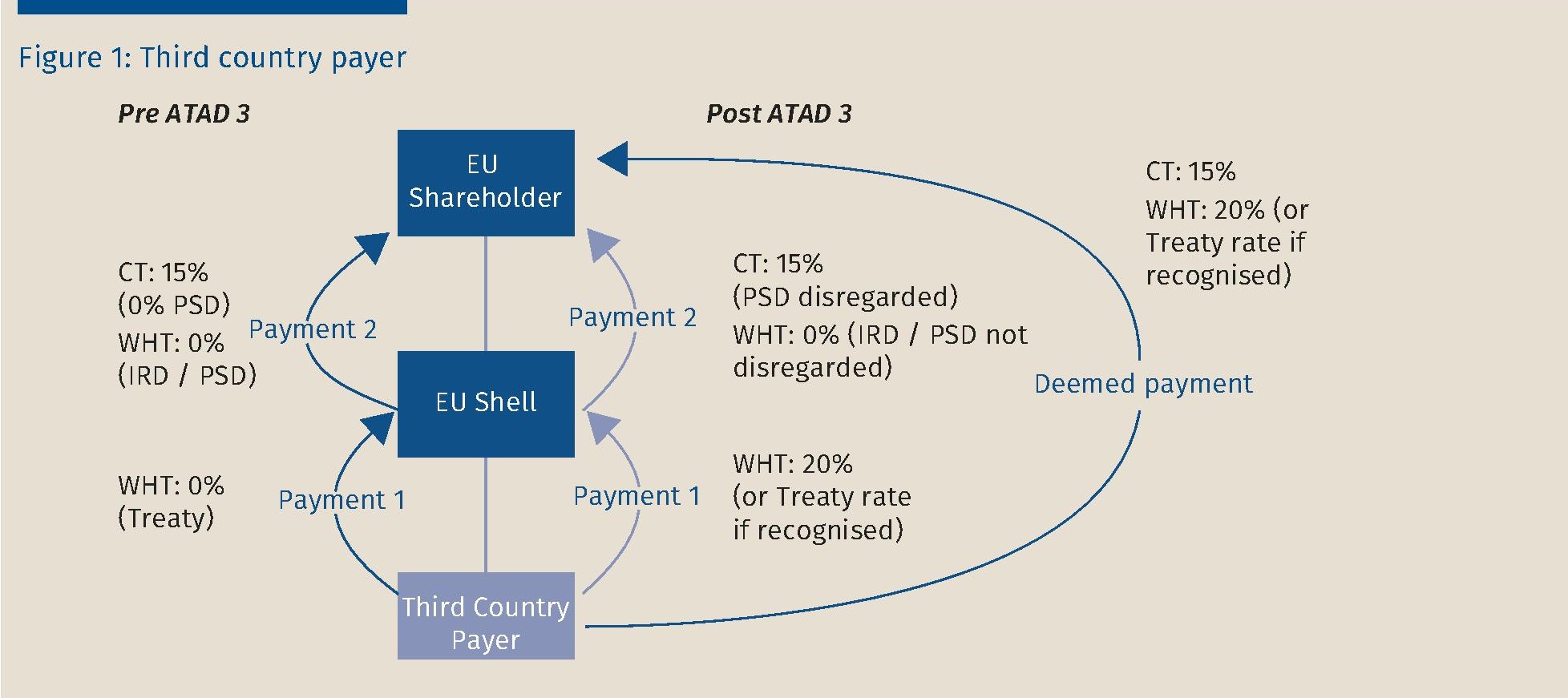

Scenario 1: third country payer

Tax treatment before the Unshell Directive

In this example, in the absence of EU Shell, EU Shareholder would have suffered a 20% withholding tax (WHT) on the direct payment of interest or a dividend by Third Country Payer.

The introduction of EU Shell eliminates WHT in the structure due to the benefits and reliefs provided by the double tax treaty between the third country and the state of residence of EU Shell in respect of payment 1 and by the EU Directives in respect of payment 2.

We have assumed that there is no corporation tax at the level of EU Shell because of either the application of a relevant participation exemption or the availability of a deduction for the onward payment under the domestic law in the state of residence of EU Shell.

How the Directive is intended to apply

The preamble suggests that the Directive would apply in the following way:

- Third country payer: The third country jurisdiction in which Third Country Payer is resident may apply WHT to payment 1 to the extent applicable under its domestic tax law or may apply a reduced level of WHT under the double tax treaty between the third country and the jurisdiction of residence of EU Shareholder.

- EU Shell: EU Shell will be taxable on payment 1 to the extent applicable under its domestic tax law.

- EU Shareholder: EU Shareholder will be taxable on payment 1 under its domestic tax law as if it had accrued to EU Shareholder directly, with credit for WHT deducted at source from payment 1 in accordance with the relevant treaty with the third country and credit for any tax paid by EU Shell.

Will the Directive achieve its objective?

The aim of the Directive is primarily to remove the WHT benefit of inserting EU Shell. In this case, that objective is purely aspirational. The preamble suggests that the third country jurisdiction "may" impose a WHT under its domestic law or "may" apply its treaty, if any, with the jurisdiction of EU Shareholder. The Directive (in article 12) seeks to enforce this treatment by imposing an obligation on the jurisdiction of EU Shell to deny EU Shell a tax residence certificate or to issue a qualified certificate. But in a case where the treaty between the third country and the jurisdiction of residence of EU Shell provides relief from WHT on payment 1, it is difficult to see how the third country ignores those treaty obligations given that, ex hypothesi, EU Shell meets the requirements for relief.

The Directive also requires EU member states to impose additional tax on EU Shareholder on payment 1 (in our example, at 15%). The preamble suggests that credit for WHT deducted at source from payment 1 is available against that tax. In our example, if credit is available, the credit for WHT imposed by the third country should eliminate the additional corporate tax liability. However, the Directive itself (in article 11) does not expressly require the EU member state in which EU Shareholder is resident to grant any credit. Furthermore, other than the general provision that EU Shareholder is to be taxed as if it had received the payment directly, article 11 simply refers to any tax charge being without prejudice to the provisions of any treaty between the third country and the state of residence of the EU Shareholder. That treaty is unlikely to require credit to be given for WHT on a payment which remains beneficially owned by EU Shell.

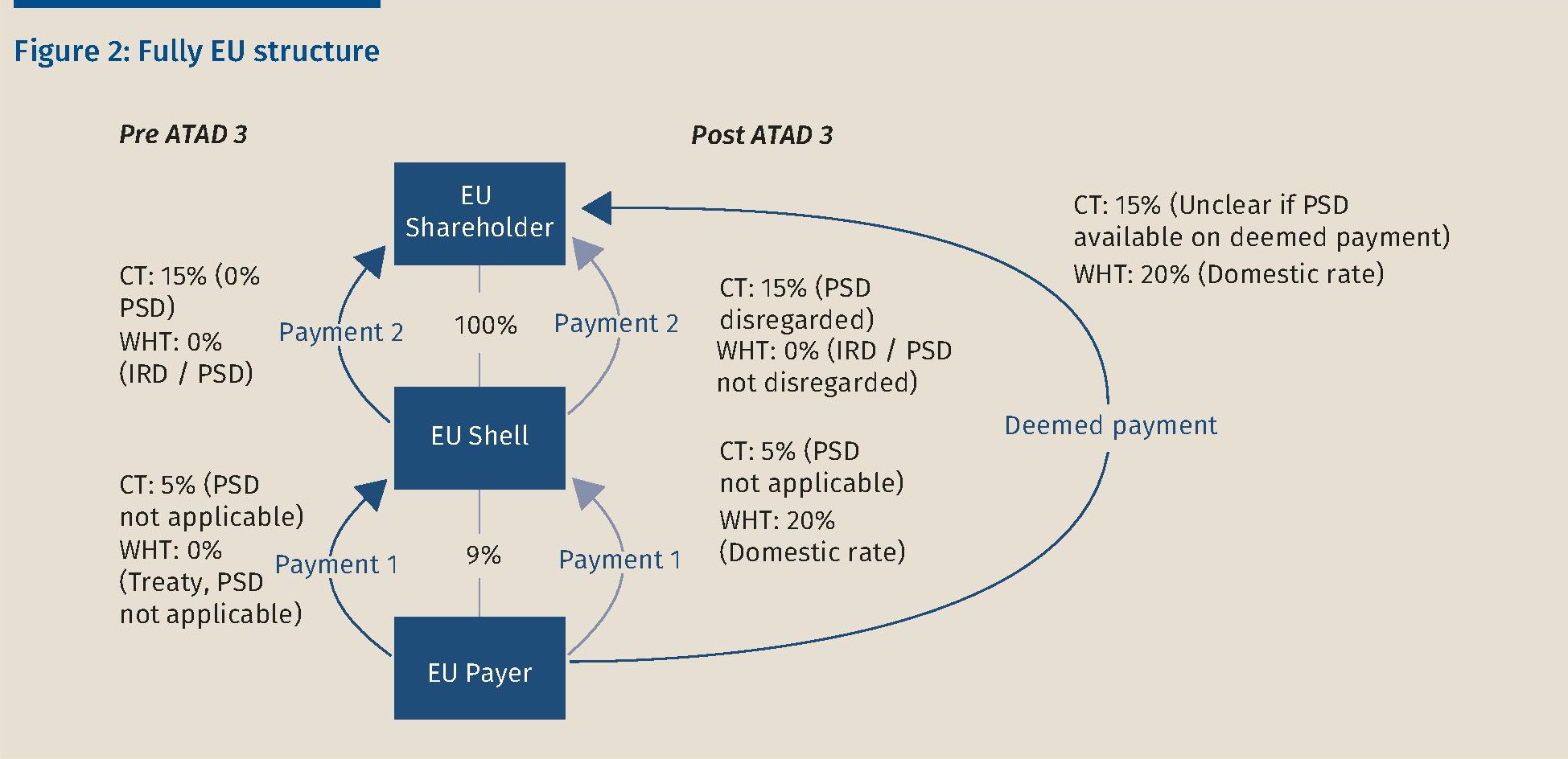

Tax treatment before the Unshell Directive

In this second example, in the absence of EU Shell, EU Shareholder would have suffered a 20% WHT on a direct payment of interest or dividends by EU Payer. (We have assumed that the group holds only 9% of the capital in EU Payer, and so payments of dividends and interest do not benefit from the EU Directives.)

The introduction of EU Shell eliminates WHT in the structure due to the benefits and reliefs provided by the double tax treaty between the EU member state in which EU Payer is resident and the jurisdiction of EU Shell in respect of payment 1 and by the EU Directives in respect of payment 2.

We have assumed that EU Shareholder pays corporation tax on interest and dividends at 15%, and, where the PSD does not apply, EU Shell pays corporation tax on dividends at 5%.

How the Directive is intended to apply

The preamble suggests that the Directive would apply in the following way:

- EU Payer: The state of residence of EU Payer may withhold tax under its domestic tax law "to the extent it cannot identify whether the shareholder is in the EU".

- EU Shell: EU Shell will be taxable on payment 1 in its jurisdiction to the extent applicable under domestic tax law.

- EU Shareholder: EU Shareholder will be taxable on payment 1 under the domestic tax law of its state of residence as if the payment had accrued to EU Shareholder directly, subject to a credit for any WHT deducted at source or tax paid by EU Shell.

Will the Directive achieve its objective?

In an all-EU structure, the effects of the provisions of ATAD 3 are to some extent clearer.

Article 11 requires the EU member state in which EU Payer is resident to disregard its treaty with the state in which EU Shell is resident. So, on our facts, EU Payer is required to withhold tax at 20% from payment 1. This is subject to qualification in the preamble – but not expressly addressed in the Directive – that a WHT may not apply if EU Payer can identify EU Shareholders. We assume this is a reference to the possibility that the EU Directives may be treated as applying in appropriate circumstances (not on our facts, but see "Issues" below).

EU Shareholder is required to pay tax on payment 1 as if it had accrued directly to it, on our facts at 15%. Once again, with credit for WHT deducted at source or tax paid by EU Shell, there should be no further tax to pay. In the case of an EU Payer, article 11(2) expressly requires the EU member state in which EU Shareholder is resident to give credit for corporation the tax on payment 1 paid by EU Shell (5% on our facts). Whether a credit is available for any WHT deducted at source is less clear and would seem dependent on the general provision (in article 11(2)) that tax shall be charged by the EU member state in which EU Shareholder is resident as if payment 1 had accrued directly to EU Shareholder in accordance with its national law.

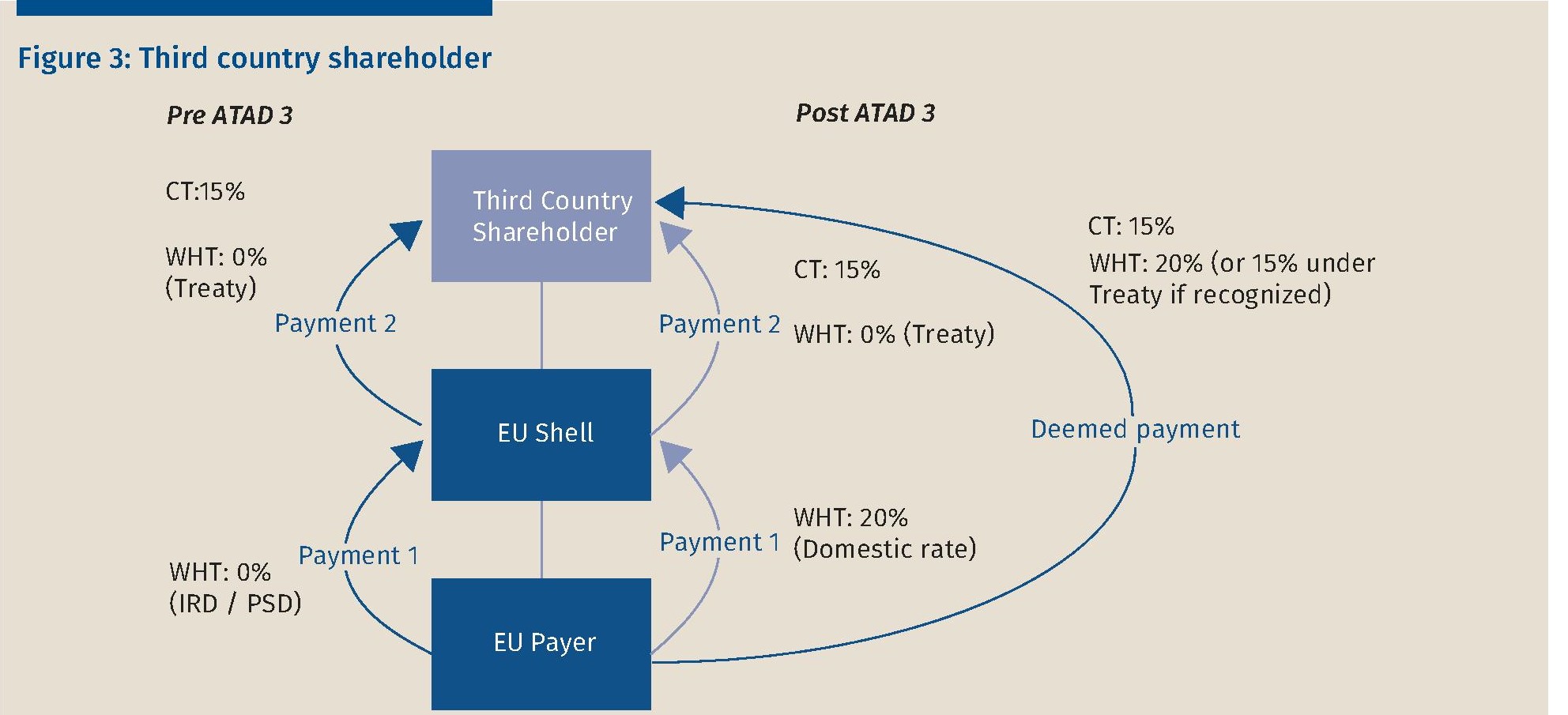

Scenario 3: third country shareholder

Tax treatment before the Unshell Directive

In this example, in the absence of EU Shell, Third Country Shareholder would suffer 20% WHT on a direct payment of interest or dividends by EU Payer under domestic law but that rate would be reduced to 15% under the applicable treaty.

The introduction of EU Shell eliminates WHT in the structure due to the benefits and reliefs provided by the EU Directives in respect of payment 1, and by the double tax treaty between the third country and the jurisdiction of the EU Shell in respect of payment 2.

How the Directive is intended to apply

The preamble suggests that the Directive would apply in the following way:

- EU Payer: EU Payer will deduct WHT from payment 1 in accordance with the double tax treaty between the EU member state in which EU Payer is resident and the third country in which Third Country Shareholder is resident or, in the absence of a treaty, in accordance with domestic tax law.

- EU Shell: EU Shell will be taxable on payment 1 in its jurisdiction under its domestic tax law.

- Third Country Shareholder: The third country jurisdiction "may be asked" to apply the double tax treaty in force with the EU member state in which the EU Payer is resident in order to provide relief for WHT imposed on payment 1.

Will the Directive achieve its objective?

The preamble accompanying this example offers an isolated indication that the EU Commission is aware of the Directive’s limitations. It states that the payment "will" be subject to WHT according to any double tax treaty in place between the EU member state of the EU Payer and third country and acknowledges that the jurisdiction of the third country "may be asked" to apply the treaty in force (for the purposes of determining credit or relief for WHT suffered at source).

The Directive itself is more equivocal. It requires (in article 11) that the EU Payer withhold tax in accordance with the domestic law of the relevant EU member state, without prejudice to the application of the treaty between that state and the third country. The difficulty is of course that that treaty will not apply. While the Directive may require EU member states to apply the tax rules as if the treaty applied, it cannot impose an obligation on a third country to recognise that treatment.

So, on our facts, EU Payer may deduct WHT at 20% from payment 1 if domestic rules apply or 15% if the treaty with the third country is deemed to apply. However, it remains to be seen whether a third country will be prepared to adopt this "look-through" treatment and in effect apply the Directive by giving a credit for the WHT. That seems particularly uncertain in circumstances where the payment that Third Country Shareholder receives (i.e. payment 2) falls within its treaty with the EU member state of EU Shell and that treaty permits no WHT and requires no credit to be given by the third country.

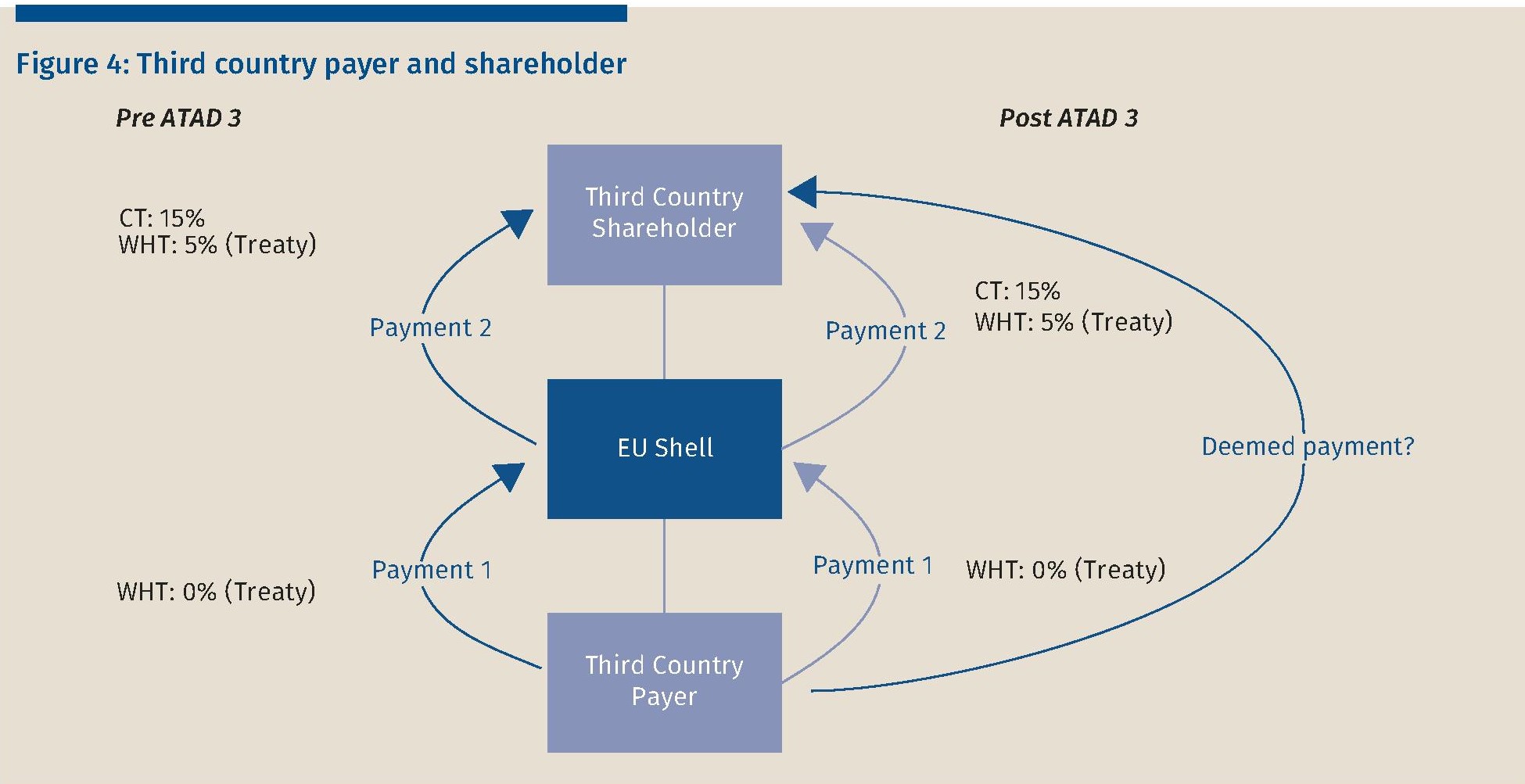

Scenario 4: third country payer and shareholder

Tax treatment before the Unshell Directive

In this final example, in the absence of EU Shell, the direct payment of interest and dividends between Third Country Payer and Third Country Shareholder would suffer 20% WHT.

The introduction of EU Shell reduces WHT in the structure due to the benefits and reliefs provided by the double tax treaty between the third country in which Third Country Payer is resident and the EU member state in which EU Shell is resident in respect of payment 1 and by the double tax treaty between the EU member state in which EU Shell is resident and third country in which Third Country Shareholder is resident in respect of payment 2.

How the Directive is intended to apply

The preamble suggests that the Directive would apply in the following way:

- Third Country Payer: The Third Country Payer jurisdiction may apply withholding tax to payment 1 to the extent applicable under its domestic tax law or in accordance with its treaty with Third Country Shareholder "if it wishes to look through the EU Shell entity".

- EU Shell: EU Shell will be taxable on payment 1 in its jurisdiction under its domestic tax law.

- Third Country Shareholder: The Third Country Shareholder jurisdiction "may consider applying a treaty in force with the source jurisdiction in order to provide relief".

Will the Directive achieve its objective?

The consequences of this example will depend on the treatment adopted by the third countries involved. As the preamble suggests by the terms "if it wishes" and "not compelled" there is a limit to the consequences that an EU directive can impose where third countries are involved.

The Directive itself does not attempt to impose obligations that would affect the operation of treaties in place between the third countries in this example and the EU member state in which EU Shell is resident. The only obligation that the Directive imposes on EU Shell is that the relevant EU member state should deny EU Shell a tax residence certificate or issue a qualified certificate.

Issues

The treatment of payment 1

One of the basic premises of the taxation provisions of the Unshell Directive is to impose tax on the inward payment (i.e. payment 1 in our examples) on a "look-through basis" that ignores the interposition of EU Shell and treats the payment as if it had been received by the ultimate shareholder. However, as our examples show, the application of this premise is inconsistent and at best half-hearted.

Double tax treaties

In a case where a double tax treaty would otherwise apply to a payment within the structure, the Unshell Directive conflicts with the application of that treaty. That is, at least in theory, less problematic where the parties are all resident in EU member states to which the Unshell Directive might apply, but it presents material difficulties in cases where one or more parties are resident in a third country.

It needs to be remembered that the Unshell Directive is intended to operate in circumstances where the concept of "beneficial ownership" in the dividends and interest articles of treaties that follow the OECD model or the application of the principal purpose test is insufficient to deprive the structure of its treaty benefits. It will therefore apply in cases where the traditional analysis would respect the application of the relevant treaties (with the jurisdiction of the EU Shell) to payment 1 and payment 2. In those circumstances, why would a third country ignore its treaty obligations or seek to tax the arrangements on the basis of a treaty (between the jurisdictions of the Payer and the Shareholder) which does not apply?

The Directive acknowledges this fact in that it does not impose a direct obligation on the EU member state in which EU Shell is resident to disapply its treaties with third countries. However, it does seek to interfere with treatment of payments under those treaties by requiring that EU member state not to issue a certificate of tax residence or to issue a qualified certificate. This is in circumstances where, by definition, the relevant treaty benefits are available.

EU Directives

Whilst the Unshell Directive imposes an obligation on EU member states (other than that of EU Shell) to disregard the operative articles of the EU Directives in their application to EU Shell, the Directive is silent on the application of the EU Directives to a deemed payment to EU Shareholders.

As regards the application of the EU Directives to the deemed receipt of payment 1, the preamble notes that an EU Payer may apply WHT on the payment "to the extent it cannot identify whether the [EU Shell’s] shareholder(s) are in the EU". This seems to suggest that if the EU Payer can identify the ultimate shareholders as being resident in an EU member state, it may apply the IRD or PSD to allow the payment to be made free from WHT on a "look-through" basis.

For payments of interest, the IRD applies to payments between associated companies, which requires one company to have a "direct" minimum holding in the capital of the other (or a third company having such a holding in both). For payments of dividends, the PSD defines a parent as the company holding at least 10% of the capital of another company (its subsidiary).

The Directive does not, however, address how these requirements are to apply to the deemed receipt of payment 1 beyond the general provision requiring the EU member state in which the shareholder is resident to tax payment 1 as if it had accrued directly to those shareholders.

The treatment of payment 2

If the Unshell Directive were to adopt a consistent approach, it might also be expected that the corollary of treating payment 1 as accruing directly to the shareholders in EU Shell would be to exclude the receipt of payment 2 from taxation in the hands of the shareholder to the extent that it represents the same income in economic terms.

The Directive does not appear to take that approach. The Directive does not oblige EU member states in which a shareholder is resident to exclude payment 2 from tax to any extent and expressly requires such states to disregard the application of operative articles of the EU Directives and any tax treaty with the jurisdiction of EU Shell. Thus the Directive seems to assume that payment 2 remains fully taxable in the hands of EU Shareholders with all the attendant risks of double taxation.

EU Shell

The Unshell Directive contains few provisions regarding the tax treatment of the payments by EU Shell itself other than the obligations on the EU member state in which EU Shell is resident regarding certificates of tax residence. In particular, the Directive does not seek to disregard the application of the EU Directives by EU Shell (in obtaining credit or exemption for tax on payment 1 or relief from WHT on payment 2). Furthermore, the Directive assumes that EU member states in which shareholders are resident will give credit for tax paid by EU Shell on the receipt for payment 1 from an EU Payer (but not from Third Country Payer).

Concluding remarks

There is some way to go before the Unshell Directive is finalised. Working through the examples and how they might work in practice demonstrates how potentially severe the tax consequences could be for groups whose EU holding companies fail to meet the substance standards set by the current draft of the Directive. The stated aim of the Directive was to neutralise the tax impact of the use of shell companies, with consequences that are proportionate. In fact, the scenarios included in the preamble could in practice give rise to layers of double taxation and therefore penalise the use of such structures, rather than merely neutralising the effect of the shell entity.

A number of questions remain as to how the Unshell Directive measures can be effectively applied where third countries are involved in structures that include EU shell entities. The EU will not be able to rely on third countries applying their domestic tax laws and bilateral tax treaties as if the EU shell did not exist.

Meanwhile, the EU Commission has indicated an intention to propose similar rules to tackle the use of non-EU shell entities. The implementation of such a regime is likely to prove even more challenging. It may be that enforcement of any such proposals can only be achieved through the rather blunt instrument of the "blacklist" of non-cooperative jurisdictions. It remains to be seen whether any such proposals will have implications for UK holding companies.