Take private transactions

23 September 2020Part 1: Sponsor perspective

The majority of acquisitions by PE sponsors in recent times have involved highly competitive auctions, ending with a sale and purchase agreement, which, although privately negotiated, will generally follow market conventions in form and content. Once signed, this agreement guarantees that the buyer will acquire the asset (subject to whatever conditions need to be satisfied, waived or fulfilled by closing).

However, prior to the onset of the Covid-19 crisis, an increasing number of takeovers of listed companies by sponsors (P2Ps) had been seen in the market and there is speculation that this form of acquisition could be one of the first to see activity levels rising as the crisis bottoms-out, with opportunities expected to arise as a result of depressed share prices and companies needing capital to invest in growing and rebuilding their businesses.

A P2P can, on the face of it, look quite different to an auction sale both in terms of the process and the deal terms, in particular the inability to get exclusivity and the difficulty in getting private sale style deal protections. This may make sponsors hesitate about devoting significant time and resource to pursuing potential P2P opportunities.

However, the core terms on which private M&A deals tend to get signed are not in fact that different to P2P transactions and once a sponsor is more familiar with the dynamics of a public M&A process, it can offer advantages over traditional auctions. To illustrate this, set out below is a high level summary of certain typical features of a private M&A deal and how they compare to a typical P2P transaction:

|

Deal feature |

Typical private M&A deal position |

Typical P2P position |

|

Balance sheet |

Addressed through:

|

No leakage provisions or ability to use completion accounts, but: |

|

Availability of extensive termination rights and MAC provision |

Governed by market practice and bargaining strength of |

MAC provisions can be included in the offer terms, but the Takeover Code makes it difficult to use them in practice (the deal timetable can be used to create a limited walkaway right though) |

|

Certainty of funds |

Sellers obtain comfort through a combination of contractual protection and diligence on |

Formal Cash confirmation is a requirement of the Takeover Code |

|

Management incentivisation arrangements |

Negotiated with management alongside the main sale terms and documented at the same time |

Normally deferred until after the P2P closes, as otherwise disclosure of the agreed terms and independent target shareholder vote is required |

|

Due diligence process |

Addressed through: |

Requirements of Listing Rules and MAR disclosure of inside information means substantial information in public domain Confirmatory DD common but competing bidders have a right to equal access under the Takeover Code, which can restrain target cooperation |

|

Availability of break fee from target

|

Governed by market |

Not permitted other than where bidder invited by target as a “white knight” bidder or in a formal sale process |

|

Business warranties and tax covenant

|

Customarily given by some or all of the sellers, often with very limited recourse backed-up by insurance policy |

Technically possible but not seen in practice |

|

Deal certainty

|

Period of exclusivity to negotiate final sale terms possible (although not always agreed by the sellers, depending on deal dynamics) and buyer contractually committed once sale agreement signed (subject to conditions) |

Not possible unless an existing controlling shareholder is selling |

More details on how these features are addressed in a typical P2P and details on how the typical process and timetable for a P2P runs are set out below.

Identifying and valuing the asset

Public listed companies are required to disclose very significant levels of information in order that the market can price the shares. Immediately this means that targets can be identified and an assessment can be made as to whether the PE sponsor believes the market is undervaluing the target company. Public companies tend not to carry as much debt such that, with some relatively basic financial engineering, a premium can be justified. Typically speaking, on a P2P transaction we would expect to see a premium over the target’s volume weighted average price of 30-40%, although this can vary from transaction to transaction.

We are often asked how much due diligence can be carried out on the target company. We always recommend that full advantage is taken of available public information before meaningful engagement with the target. This way the initial due diligence request can be focussed on only those matters which are essential to validate the valuation and transaction assumptions. Once a process begins and the target has engaged constructively, it is often possible to delve into further detail. However, because the Code requires a target company to give equal access to other potential bidders (even if they are competitors) targets can be reluctant to provide full due diligence access, even if the equal access concern is often amplified and used as a screen.

Most public companies will not provide due diligence information unless and until the prospective bidder has put forward an indicative offer price which the target board believes it could recommend to shareholders. Also, the target board will generally insist that the non-disclosure agreement which has to be signed in order to get access to information will contain a standstill restricting the prospective bidder from buying shares, making a hostile bid or contacting target shareholders. As most P2P transactions are recommended this type of NDA is generally agreed upon.

The all-important approach

Consider it from the perspective of the target board

Unless the listed company has put itself up for sale, by publicly announcing a formal sale process or making an informal strategic review announcement (in which event an investment bank will generally be engaged to run a process), the company may be blissfully unaware it is a takeover target. Of course, in many cases there will be media speculation or investment banks may be bringing prospective targets to the PE sponsor but that does not mean the target wants to be the subject of a takeover.

Under the Code, any approach is expected to be made to the chair of the company who will invariably be a non-executive director. Upon an approach, the chair will brief the other directors and as a group they will decide whether to engage in discussions and on what terms. If the board decides to engage, it is required by the Code to appoint an independent financial adviser whose advice will inform and support the target board and will be made known to the target shareholders.

Understanding your audience

UK companies listed on the London Stock Exchange or AIM have a unitary board structure consisting of a mix of executives and non-executive directors (who generally form a majority). From a strict legal perspective, executive and non-executive directors have the same duties and responsibilities. However, in practice non-executive directors will feel a particular responsibility towards all stakeholders in the company upon a takeover. After all, unlike the executives, their tenure will, more often than not, come to end upon the takeover completing; and they will be judged on whether they properly discharged their duties and obtained the best possible price.

Consequently target boards can be reluctant to engage with an unsolicited approach from a PE bidder, especially where the sponsor is perceived to be trying to take advantage of a share slump following some bad news specific to the company or some sector-wide re-rating. Listed company boards tend to look at the premium to where the shares trade (or have traded in the recent past) whereas PE buyers look towards fundamentals of valuation, just as they do with private processes.

We have seen a number of instances where increasingly higher approaches have been rejected by the target board on the basis that the offer is materially, significantly or fundamentally undervaluing the company. These rejection letters can leave the buyer having to decipher the wording of the letter to figure out just how far off a recommendable price their offer is. An understandable concern from the perspective of the target board is that the price may only go down rather than up in due diligence and giving access to due diligence heightens leak risk.

In our experience, target boards do not generally like being lectured by a prospective buyer on the need to put a proposal to shareholders in order to satisfy their fiduciary duties; and this kind of threat can ring hollow when a PE buyer is unable or unwilling to go public with a hostile bid or bear-hug announcement (and the target knows this).

It can be hard to know whether target reluctance to engage is due to a forceful director (i.e. the chair) leading the board or the entire board being aligned. Having a strategic insight into the likely attitude of individual board members can assist in knowing how to make an approach and what buttons to press in order to get traction. We recommend PE sponsors prioritise soft due diligence in this area as much as possible. Having or finding (i.e. through advisers or existing networks) good and trusted connections with persons on the board, especially the chair can be very impactful.

Breaking cover and leak announcements

The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and the Takeover Panel Executive (Panel) are determined to avoid false markets and avoid trading in securities by persons with inside information about the possible offer. This regulatory objective creates a tension between the interests of PE sponsors and target companies (not wanting to be forced into premature announcements); and the Panel and the FCA (seeking to limit insider trading)1.

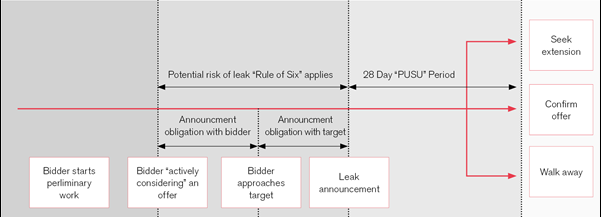

In addition, the Code has some strict timing rules over the length of time that a target company can be the subject of the uncertainty which is created by a possible takeover offer (during which period the target is also subject to obligations such as not being able to take action which may frustrate the possible offer), the so called “siege principle”.

The combination of the siege principle and the rules designed to prevent false markets means that:

- The circle of insiders about an offer must be kept to an absolute minimum.

- If there is, or is considered by the Panel to have been, a leak then an announcement must be released immediately notifying the market that an offer may be made.

- The announcement must be released by the prospective bidder if it has not yet made an approach; or by the target, if it has been approached (unless that approach has been unequivocally rejected by the target in which case responsibility reverts to the prospective bidder).

- Thereafter the bidder has just 28 days to: announce a fully financed offer; obtain an extension of time to do so; or make a no intention to bid statement (whereupon it will be restricted from bidding for 6 months) – the so called “put up or shut up” rule or “PUSU”.

Click to enlarge the image.

It is fair to say that the operation of these rules is not much liked by potential bidders. Equally however, target companies do not like being prematurely “put in play”. From a sponsor perspective though, there should be nothing much to fear provided:

- Early advice is taken on the relevant rules before any P2P project goes beyond routine early stage desktop assessment of an investment opportunity.

- Routine early stage internal discussions are limited to PE sponsor executives and employees (it may not be possible to reach out to your circle of contacts who you might often consult with on possible investment opportunities until later in the process).

- Once the point is reached where an announcement might have to be made before an approach, the so-called stage of “active consideration”, ensure that you fully understand the rules about widening the circle of insiders, making announcements and consulting the Panel. Normally no more than six external parties (such as shareholders or potential providers of finance) can be approached unless the Panel consents - the so called “Rule of Six”.

- Note that what the Panel and Code classifies as active consideration or an approach is often very different to what the PE sponsor may expect and it’s the Panel’s opinion that counts.

Some P2P transactions remain secret and unannounced unless and until the firm offer announcement is made; however, some start with a possible offer (or leak) announcement, a PUSU period (which is extended) and eventually a firm offer announcement - of 155 P2Ps that have been announced since 2007, 21 of these started with a leak announcement. In other words, whilst many PE sponsors may feel an initial aversion to the Code disclosure and PUSU rules, in practice they tend not to be fatal to transactions provided the rules are understood and addressed properly.

Off to the races

Unlike a private M&A deal, takeovers have structured timetables. This can be confusing because the timetable depends upon several factors:

- Whether the deal is structured as a takeover offer or a target scheme of arrangement.

- What regulatory conditions are required to be satisfied and how long this will take.

- Whether the takeover is recommended, hostile or becomes competitive due to the emergence of a competitor.

However, most P2P’s are carried out by means of a target scheme of arrangement which is recommended by the target board without any rival bidders appearing after the offer is announced.

Under this structure, the scheme must be approved by a 75% majority in value comprising a simple majority in number of those attending and voting at a meeting of target shareholders. Shares held by the bidder cannot count in these majorities, so whilst stake building may deter a competing bidder it does not assist in getting the shareholder approvals. It is customary to get target directors (and institutional shareholders if possible) to give non-binding letters of support or, preferably, irrevocable undertakings to vote in favour of the scheme. It is normal for these commitments to fall away in the event of a higher offer being announced by an interloper.

Once a firm offer announcement is released, the scheme circular to convene the shareholder meeting must be convened within 28 days. Once the vote has been held, the scheme becomes effective provided a court sanctions the scheme and the court order is filed. On occasions the court is petitioned to withhold consent (as happened on the Inmarsat P2P scheme, although the court did sanction the scheme in that instance nonetheless) but such instances are rare and in most instances the court hearing is a routine event.

If the regulatory conditions have not been satisfied, fulfilled or waived by the time of shareholder vote (and the vote is therefore subject to the conditions subsequently being satisfied, fulfilled or waived), it is customary to delay the court sanction hearing until such time as completion can take place.

The ugly interloper

With a scheme, a counter-bidder can come forward with a competing proposal at any time until the court order is filed, in which event the deal might be lost. Whilst this cannot happen with a private M&A deal where the sale and purchase agreement has been signed, this risk (whilst genuine) has to be balanced against the following practical observations:

- The original bidder has first mover advantage. It will be further advanced with due diligence and once its firm offer is announced, the target will have certainty that the offer will proceed if approved by the target shareholders (unless there is perceived to be significant risk the regulatory conditions will not be met).

- Even if a second bid is made, the first bidder will have the opportunity to increase its offer (provided it has not tied its hands by making a statement that its offer is final and/or will not be increased in any circumstances).

- If the first bidder has acquired a strategic stake in the target with a view towards assisting its offer to succeed (albeit rare with PE sponsors), then it can sell that stake to the second bidder rather than increase its offer or it can use it to vote against the second bidder’s offer.

- Whilst it is extremely frustrating to expend significant time and expense on a transaction that does not ultimately succeed because a higher bid is made, this is no different to a private auction where a PE sponsor carries out all the work and loses out in the final round or in a contract race after final bids (other than the fact that it is a public process).

Shutting out the interloper and shortening the timetable

In some situations, a PE sponsor may decide to acquire a significant block of shares and/or announce a contractual takeover offer rather than elect to use a scheme of arrangement. It might choose to do so because:

- Shares acquired in the market count towards the 50% voting control threshold required to declare the offer unconditional, the so called “acceptance condition”, alongside other acceptances to the offer, thus boosting its chances of reaching that threshold.

- The first closing date of the offer can be set at 21 days, so, in theory, the acceptance condition can be satisfied as soon as 21 days after the offer document is published and, as all other conditions (e.g. regulatory conditions) must normally be satisfied within 21 days of the acceptance condition being satisfied, the offer can become “unconditional in all respects” as quickly as 42 days after the offer document is published.

Of course, these are all best case scenarios and the following should be noted:

- Unless the bid is recommended by the target, the offer document (which starts the formal timetable) cannot be posted earlier than 14 days (nor later than 28 days) after the firm offer announcement is released, which gives the target board time in a hostile bid to lobby shareholders against accepting the offer and to put forward its defence document (which must be published within 14 days of the offer document being published); however, hostile takeovers by PE sponsors are very rare (LPA’s sometimes prohibit them).

- Unless the first bidder can satisfy the acceptance condition on the first or any subsequent acceptance date in the typical 60 day offer timetable, a second bidder can announce a counter bid, after which both bidders will move to a new timetable determined by the second bidder’s firm offer announcement.

- Delays in regulatory approvals may mean that the timetable for the offer gets frozen (normally at day 37), with the result that the whole timetable is extended giving more time for interlopers.

In a recommended takeover offer it is customary to get target shareholders to give non-binding letters of support or irrevocable undertakings to accept the offer once made. It would be very unusual for these commitments not to fall away in the event of a higher offer being announced by an interloper.

Working out the best transaction structure and strategy for a P2P will depend upon the specific dynamics and circumstances for that particular P2P at the time.

Transaction agreements, break fees and poison pills

Under the Code, target companies are not permitted to:

- Enter into offer-related agreements with a bidder, which rules out break fees (save in exceptional circumstances), matching rights and similar arrangements designed to prefer the bidder and restrict the target.

- Take any action which might frustrate a possible takeover without shareholder consent, which prevents the target from issuing additional shares, disposing of material assets or entering into contracts other than in the ordinary course of business.

This does not restrict clean team agreements designed to share confidential information on a restricted basis to secure competition clearances.

MAC and other protective conditions

Under the Code, a bidder cannot invoke a condition to an offer (other than certain anti-trust conditions) unless the circumstances allowing it to invoke the condition are “of material significance to the offeror in the context of the offer”.

The Panel established (in its ruling on WPP Group plc’s 2001 offer for Tempus Group plc) that meeting this test for a general MAC condition requires an “adverse change of very considerable significance striking at the heart of the purpose of the transaction in question”. The bar a bidder has to clear is therefore very high.

This approach has recently been reconfirmed by the Panel in Statement 2020/4 when it ruled that Brigadier Acquisition Company Limited could not invoke certain conditions, including a MAC, to its offer to acquire Moss Bros Group plc, despite the impact of the Covid-19 crisis.

If a bidder wants to maximise its chances of being able to lapse an offer due to a condition not being satisfied, it will need to draft the conditions carefully and consult the Panel Executive and its advisers before taking any action.

In most cases, withdrawal is simply not possible, especially if the bidder is looking to rely on a standard condition (such as a MAC) which has not been drafted with particular circumstances in mind. Even then, the Executive will look at the facts and circumstances at the time to decide whether the overriding material significance test has been met.

Sometimes, it is possible to lapse an offer by using the offer timetable where a MAC arises. For example, in a scheme the bidder can set longstop dates for key events and decline to waive these deadlines. Conversely, in a contractual offer the bidder can walk away on any closing date if the acceptance condition has not been satisfied (even if the real reason is the fact that a MAC type event has arisen).

Management and special deals

Increasingly in P2P transactions, the management incentive scheme discussions are deferred until after the transaction has closed. This is usually so that certain extra requirements of the Code can be avoided. Specifically:

- If existing management own shares and/or options in the target company (which they often do) and they are then are offered ongoing equity incentives in the Bidco which are not being made available to all shareholders, that is a so called, “special deal”.

- Ordinarily, one shareholder cannot receive a special deal unless all shareholders are offered the same special deal.

- However, the Code allows such a special deal to be offered to management provided the target’s financial adviser gives an opinion that the terms are market standard and provided the terms are subject to a confirmatory vote of approval by the target shareholders.

- If the special deal is offered to any non-management shareholder, then it cannot normally be offered (or sanctioned by a confirmatory vote of approval) save in certain exceptional circumstances where the shareholder qualifies as a so called, “joint offeror”.

Where target management are provided such a special deal, there are normally other consequences under the Code and company law:

- The management directors will have a conflict of interest and a special committee of the unaffected directors will normally be formed to consider the offer.

- If the management directors contribute to the PE Sponsor’s business plan (as they usually would on a private sale), that private plan may be discloseable to the special committee.

We will examine issues for target boards and management teams in detail in Part 2 of our P2P transactions series.

Financing

Financing a P2P is not fundamentally different to establishing secured finance for a private M&A bid. However, because a financial adviser will be required to give a public cash confirmation statement in the offer documentation the financing documents will be rigorously diligence by the financial adviser to avoid it being liable in the event of funds not being available. This means that the fund’s equity structure and draw-down mechanics will be reviewed. Also, the terms of any acquisition facilities will be reviewed and these must be on so called, “certain funds” terms with no market MAC or other draw-stops to funding. If alternative funders like debt funds are used, the diligence will be similar to that carried out in relation to the equity fund. Not all debt funds are familiar with this process so early engagement to ensure the certain funds concept is understood is critical.

We will examine structuring and financing aspects in detail in Part 3 of our P2P transactions series.

Conclusions

Once the target has agreed that the prospective bidder has put forward a recommendable proposal, most P2P transactions are fairly straightforward and proceed smoothly by way of a recommended scheme of arrangement. There are special rules to follow, some of which will be unfamiliar, but ultimately those rules create a stable framework for the offer to be made and many of the rules actually operate to the advantage of the bidder.

Unlike public M&A in some jurisdictions (e.g. the USA), there is virtually no securities litigation in UK public M&A. The Panel Executive is actively involved and issues are generally resolved promptly and fairly during the takeover. The Panel operates its own system of regulation which includes appeals from rulings and disciplinary action.

1 According to figures published by the FCA, in 2018 approximately 6.3% of unexpected potentially price-sensitive announcements (that were tested) were preceded by statistically abnormal increases in trading volumes, which is an improvement on previous statistics. The FCA considers this improvement vindication for the tougher regulatory approach it has been taking.

Get in touch