Born to be filed: delving into tax and conservation covenants

16 August 2023Henry Vane and Rebecca Rose dig into the tax treatment of conservation covenants for investors, landowners and responsible bodies.

This article first appeared in the August 2023 issue of Estates Gazette.

There is considerable excitement in the environmental and investment worlds around the potential of conservation covenants (CCs) - a legal innovation that could unlock green finance and effectively channel capital from the City to the countryside. However, this enthusiasm will count for little if CCs don't make both financial and environmental sense. This inevitably brings us sharply back from squelchy peat bogs and soaring butterfly meadows to tax. After the Government finally opened the application process to be a responsible body to enforce CCs on 27 July, now is a good time to explore the tax questions that will determine whether CCs flourish and make England and Wales their home, or end up as a forgotten legal specimen in a dusty glass case.

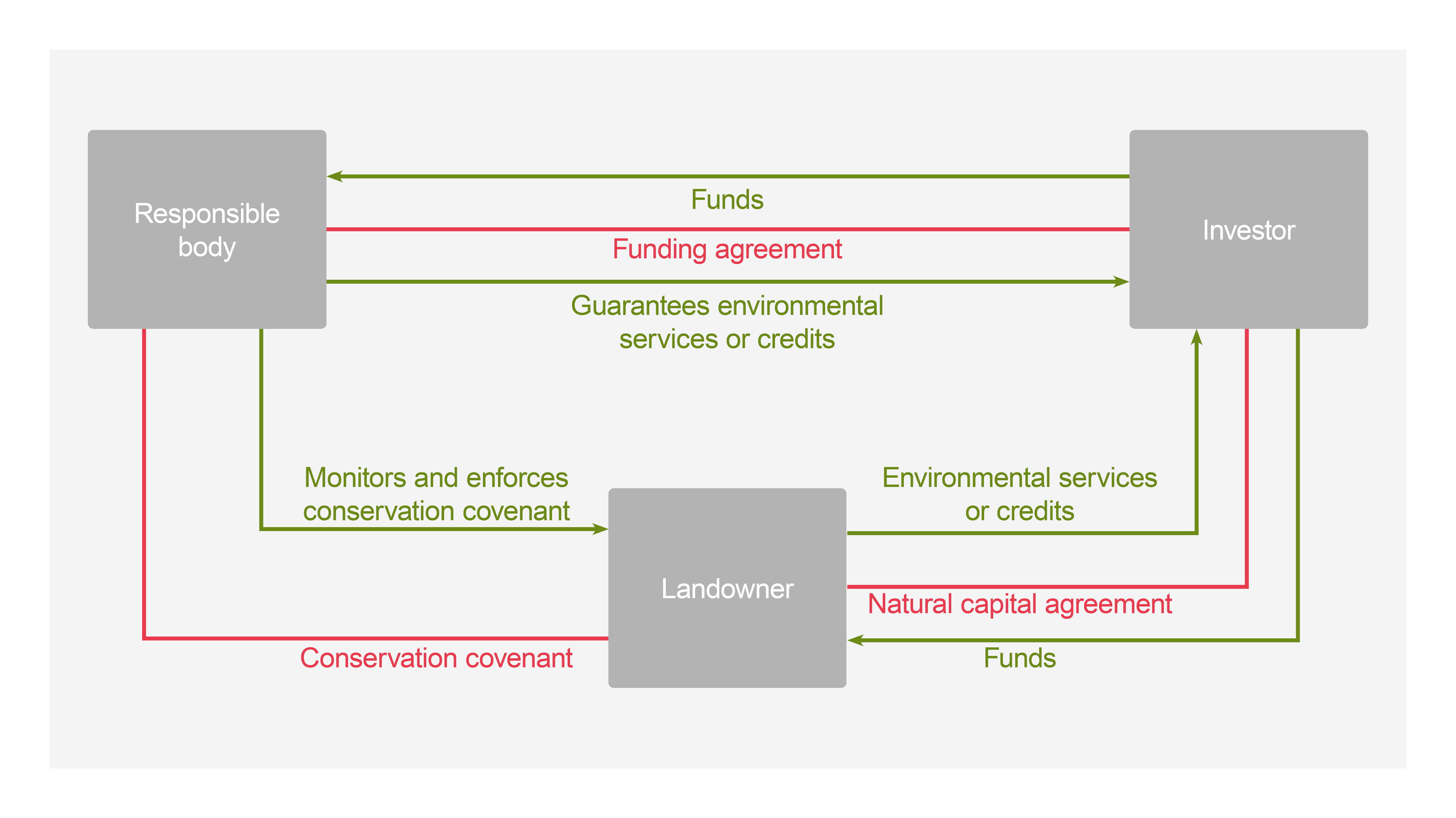

As outlined previously in "Conservation covenants for investors", we see CCs alongside natural capital agreements (NCAs) for environmental services and part of a triangle between landowner, responsible body and investor. The focus of this article is on the tax implications for each of the three parties - investors, responsible bodies and landowners.

A conservation covenant recap

Introduced into law by the Environment Act 2021, CCs are the most radical land law innovation in a generation. They are voluntary agreements (either indefinite or time-limited) between a landowner and a responsible body to manage land for a "conservation purpose" and for the public good.

In a tripartite arrangement such as that outlined above (and illustrated below), the CC between the landowner and the responsible body will set out the conservation purpose and bind the land, and under the linked NCA, the investor will buy environmental credits or services arising from the conservation purpose from the landowner. The investor will also enter into a funding agreement with the responsible body.

A key benefit of CCs for investors is that they do not need to buy or lease the land in question (a stamp duty land tax (SDLT) saving) to secure environmental credits (e.g. biodiversity net gain units) or satisfy other ESG commitments.

CCs have clear advantages over other forms of agreement:

- they bind land more tightly than typical covenants - successors in title will take subject to the positive as well as negative obligations and there is no need to own neighbouring land;

- they are more robust than contracts for environmental services (e.g. NCAs) because they bind the land and not just the parties;

- the third-party oversight by the responsible body gives investors, lenders and regulators confidence that the underlying environmental product is secure;

- they can efficiently hold together multiple landowners on the same (or potentially different) terms, with a single responsible body enforcing;

- a CC will appear on the land charges register which, although publicly available, is more private than the land registry; and

- when setting up the CC/NCA arrangement, you can choose your own enforcing responsible body.

Responsible bodies

There are currently no special tax rules for responsible bodies - they will be subject to the same tax considerations as ordinary local authorities, charities or companies (as relevant).

SDLT

SDLT is payable on the acquisition of a chargeable interest. The definition of a chargeable interest includes "the benefit of an obligation, restriction or condition affecting the value of any... estate, interest, right or power [in England or Northern Ireland]" (Wales and Scotland have separate, although similar, rules). A CC, as an obligation on the landowner to do (or not do) certain things, appears able to fall within the definition.

Nevertheless, no payment is being made by the responsible body to the landowner and, therefore, unless (a) the responsible body is a company that is connected to the landowner (and so SDLT is due on the market value of the interest); or (b) the responsible body is connected to the investor (and therefore some of the consideration paid under the NCA may be apportioned to the CC - see investor section below), no SDLT should be due.

Investors

SDLT

The responsible body provides no consideration for the CC - instead, the investor pays the landowner under the NCA in exchange for environmental credits or similar. We consider these credits are not an obligation, restriction or condition, but a product/service and so should fall outside the "chargeable interest" definition set out above. Therefore, payments under the NCA should not be subject to SDLT.

The caveat to this point is that where the responsible body is connected to the investor, a just and reasonable apportionment must be made between the amount paid for the CC and the amounts paid for the credits. In practice, we would expect what is being paid for is really the credits under the NCA rather than the CC itself, which is just a legal mechanism to bind the land.

VAT: payments to the responsible body

The services performed by the responsible body (i.e. ensuring the landowner abides by the CC terms and that the environmental services provided are valid) are, absent any specific exemption, likely to be subject to VAT if the responsible body reaches the £85,000 turnover threshold. Responsible bodies that are charities or local authorities will have to charge VAT if enforcing CCs is deemed a business activity.

VAT: payments to landowner

Whether an investor must pay VAT on its payments to a landowner will depend on what exactly the investor is buying. Compliance market credits recognised under the statutory Kyoto and EU Emissions Trading System "cap and trade" regimes are subject to VAT, and the Government's response to the biodiversity net gain (BNG) consultation suggests BNG units will be subject to VAT too. However, voluntary carbon credits are (at least currently) outside the scope of VAT.

Landowners

Inheritance tax

Retaining the inheritance tax shelter provided by agricultural property relief (APR) and business property relief is a (if not the) priority for many individual landowners (although not for corporate/institutional landowners). Without either of these reliefs, up to 40% of the land's value is taxable on inheritance.

To qualify for APR the land needs to be "occupied for agricultural purposes" and it is unclear whether taking land out of conventional agriculture and repurposing it for environmental purposes within a CC would continue to qualify. The Government is alive to this point - in its taxation of environmental land management and ecosystem services markets call for evidence (published in March 2023), it entertains the possibility that CCs might automatically qualify for APR - the outcome of this consultation will be closely watched.

Business Property Relief (BPR), meanwhile, looks at whether a landowning/farming business is predominantly trading or investment activity. Put simply, if it is predominantly trading, then BPR will be available and if it is predominantly investment it will not. It is arguable whether income from the sale of credits or other environmental services in the context of a CC is trading or investment.

CCs have the potential, therefore, to upset finely balanced tax planning. Until there is clarity - through legislation, guidance or case law - landowners will be wary of CCs and/or the price they demand will remain high.

Capital gains tax (CGT)/income tax/corporation tax

Payments received by a landowner under an NCA are in return for the supply of credits, and so should be subject to income tax (or corporation tax as relevant). This may generate a large tax bill and difficulties if the payment is made up front - in such a scenario, it may be possible to spread the tax charge over the term of the NCA (the landowner should consult its accountants).

It has been suggested that burdening land with a CC could be a part-disposal for CGT purposes. However, the responsible body provides no consideration to the landowner for entering into the CC and so no CGT charge should arise (again assuming no connection between the landowner and the responsible body/investor).

What's next?

Subject to further guidance from the Treasury, it is our view that CCs could be a tax-efficient way of structuring environmental investment, principally because no land interest is purchased so no SDLT should be payable (subject to ensuring that responsible bodies are independent from investors and landowners).

At COP26 in Glasgow in November 2021, then-chancellor Rishi Sunak appeared with a green version of the famous red box. He said the UK would become the first ever "net zero-aligned financial centre" and promised "we're providing the investment we need to deliver that ambition". Nearly two years on, Sunak's Government needs to clarify the tax issues highlighted to help that investment flow through.

The market will follow the Government's lead - if it wants people to enter into CCs to protect the soil, air, water and landscape that we all benefit from, it needs to ensure the tax treatment is clear and encourages people to nurture this new species.

Get in touch

Related content

See all related content