Remuneration and share plans: Autumn update

30 November 2020Welcome to our remuneration and share plans autumn update. In this edition we review some of the key developments from the second and third quarter of 2020 affecting executive remuneration and share plans.

- New Investment Association Principles of Remuneration

- How changes to working arrangements present new challenges for employer compliance

- Using ESG performance metrics to drive cultural change

- New prudential regime: time for investment managers to focus

- HMRC publishes research findings on tax-advantaged share schemes

- Employment tax and negative earnings

- Preparing for changes to the IR35 legislation

- The PRA and FCA Consultation Papers on amendments to their remuneration rules

If you would like discuss any of the topics in this update, please do get in touch with us.

New Investment Association principles of remuneration

It’s that time of year again - the Investment Association (the IA) published the latest version of its guidance on executive remuneration.

On 16 November, the IA published its principles of remuneration for the upcoming year (the Principles) and accompanying letter to chairs of remuneration committees, which are designed to clarify its members’ expectations on issues surrounding executive pay. It also updated its guidance on how it expects the impact of the coronavirus pandemic to be accounted for when determining pay outcomes.

This guidance is not just of interest to the listed companies to which it directly applies but is indicative also of wider trends in the remuneration context. Given the current necessary focus on Covid-19, the Principles remain largely unchanged from last year, with the exception of four key inflection points.

Shareholding requirements

Although there is no change to the level of shareholdings recommended, the IA emphasises the need for companies to clearly explain how they intend to enforce shareholding requirements, particularly in relation to former directors who are no longer employed by the company.

Pension contributions

The Principles reiterate that pension contribution rates for executive directors should be aligned to the rate of the majority of the workforce, with just two years left until the deadline for aligning incumbent directors’ contributions. The IA states that, where the contribution rate received by the executive director is 15 percent or more, it will red top any company which it considers not to have a credible plan in place to meet this deadline.

Performance metrics

The IA explains that a “significant majority” of any annual bonus should be determined in line with financial targets, rather than strategic or personal objectives – especially those which may be seen as merely “doing the day job”. The link between any non-financial metrics used and long-term value creation should be demonstrated clearly.

Despite this focus on financial performance, the IA also recognises the increasing relevance of ESG factors in company decision-making, and notes that it may be appropriate for remuneration committees to include ESG considerations when determining policies and outcomes. While it emphasises that any ESG-related performance conditions must be linked clearly to the implementation of overall company strategy, the inclusion for the first time by the IA of guidance on ESG as a performance metric is reflective of a trend that is gaining increasing traction.

Bonuses

Finally, the IA provides some useful clarity in relation to its previous guidance on bonus deferrals. Where a bonus opportunity is over 100% of an individual’s salary, the requirement to defer a portion of that bonus applies to the bonus as a whole and not just to the part of that bonus above the 100% threshold.

Additionally, the IA recommends that bad leavers should not be entitled to receive annual bonus payments.

Covid-19 guidance

The overarching themes of the IA’s Covid-19 guidance are restraint and disclosure, with a warning that failing to exercise either or both of these “may lead to workforce morale or productivity issues and also have significant reputational ramifications”.

The guidance sets out specific approaches for achieving this, but broadly the remuneration committee should make decisions with clear justifications in light of company strategy and avoid compensating executives for reduced remuneration opportunity resulting from the pandemic, either with increased opportunity in the next remuneration cycle or by adjusting policies and practices in the current cycle. Bonuses should reflect any reduction or cancellation of dividends for FY2019 as well as the level of government support received by the company.

In short, pay outcomes for executives should be commensurate with the wider context and stakeholders’ experiences.

This is representative of the overall approach taken by the IA this year in its guidance. The focus appears to be on striking a balance between incentivisation during a time which is particularly challenging for those in leadership roles, while being cognisant of the wider societal context. Underlying this approach is a need for transparency and disclosure; the appropriateness or otherwise of a remuneration committee’s decision-making can only be ascertained where those decisions are explained and fully justified.

Although this next AGM season may be a time of caution, the continued focus on stakeholder experiences and increasing openness to ESG factors present interesting opportunities for remuneration committees in the near future.

How changes to working arrangements present new challenges for employer compliance

Introduction

Over the last decade, businesses have been faced with the challenge of applying cross-border tax, social security, and payroll legislation to an increasingly internationally mobile workforce. While business travel has slowed since the outbreak of Covid-19, those challenges have not gone away, and new working arrangements have brought new complications.

In light of travel restrictions, temporary changes to the statutory residence test, which is used to determine individual taxation, were announced on 19 March (see earlier article here). In issuing the guidance, HMRC indicated that it will look sympathetically at any individual cases where the virus has caused specific issues or difficulties. This was followed by OECD guidance in April (summary provided here), which also allowed for a practical approach to be taken.

Official UK employment taxes guidance for businesses has taken much longer, and it was not until 19 August that HMRC updated its guidance in relation to the operation of PAYE and National Insurance contribution (NIC) withholding for employees working abroad. Despite the long delay, the Covid-19 concessions are niche, and very limited in their application. The concession relates only to NIC withholding for individuals employed by UK companies, forced to return to work in the UK from a country with which the UK does not have a social security agreement in place, after the first 52 weeks of their assignment. In all other cases, the guidance indicates that the regular PAYE and NIC obligations for employees working abroad apply.

Forced repatriation and travel restrictions

The OECD guidance states that if Covid-19 affects where an individual performs services, an employee’s income should be attributable to the place where the employment “used to be” performed. This is fairly clear for existing employees (especially where time back in a “home” country is temporary and clearly driven by the current climate), but the rules are less clear when it comes to new hires.

Hiring a non-UK tax resident individual to undertake work for a UK business is usually made more straight forward – the new hire is enrolled in to the company payroll, and will be subject to PAYE and Class 1 NIC withholding from day 1 (on the assumption the individual is relocating to the UK to commence work).

In cases where a new hire would be commencing work duties in the UK from day 1, but cannot do so as a result of Covid-19, there is limited guidance. There is a good argument that, as per the OECD guidance the usual UK PAYE process should apply to new hires where, but for Covid-19, the duties would, absolutely, have been undertaken in the UK (even if that employee did not perform duties in the UK previously), and so would have been UK sourced employment income.

However businesses should be aware of the implications where other jurisdictions are taking a hard line approach to withholding. The UK position for an inbound new hire is (relatively) straight forward – HMRC will always be happy for businesses to be withholding PAYE and NIC. The more complex issue may be in the location in which the new hire is based, and hiring businesses should ensure they are aware of any local payroll reporting obligations. If that jurisdiction insists on operating withholding, a UK PAYE withholding could result in a dual withholding (if steps are not taken to mitigate this).

HMRC has provided little information of any blanket approach that may be applied in the alternate scenario (a UK individual who cannot start working overseas), and our view is that, if a PAYE obligation would have otherwise arisen as a result of this individual working in the UK, businesses should request advance clearance from the revenue before ignoring this obligation on the basis of the OECD guidance.

Requests for flexible working arrangements

With much of the workforce forced to work from home over the past year, requests for more flexible cross-border arrangements are becoming increasingly common.

The tax implications of these arrangements range from simple to incredibly complex. Individuals who retain ties to the UK, or visit the UK for personal reasons, may remain UK tax resident, and so could be taxable on worldwide income in any case. Even in cases where individuals become UK non-resident, any substantive UK workdays will be classified as UK ‘sourced’, and so UK taxable.

In most cases, where an individual’s role (or employment relationship with the UK company) has not changed, the UK company will have a continued obligation to withhold PAYE (and the social security position will generally need even more detailed analysis, based on the travel pattern).

Often more complicated still are the compliance requirements in the second country. A company may be required to take actions such registering as an employer (e.g. nationally or within the local municipality/state), operating payroll and other benefits reporting (and ensuring any dual withholding is mitigated), setting up a local pension scheme (which they should ensure does not create any further UK tax complications, such as employer contributions being reclassified as UK taxable income), or filing local tax returns.

Businesses will also need to consider the role of the individual, and the permanent establishment implications of having employees performing their main role in another jurisdiction. Creating a non-UK PE of a UK company can lead to corporate compliance obligations (and potentially a corporate tax liability).

How should businesses approach these challenges?

- Manage working arrangements up front. Often compliance failures can be mitigated if arrangements are known about before they are enacted (and there can often be opportunities for businesses to optimise the tax position, which can be beneficial for the business, and the employee). It follows therefore that the sooner employers are aware of a potential cross-border situation the better, so the employer should be clear in communications to employees that they should not be working internationally without approval.

- Seek advice. Businesses should consider the personal tax, employment tax, corporation tax, social security, and payroll implications in both the UK and the overseas jurisdiction (in addition to other factors such as local employment law or regulatory considerations).

- Set clear guidelines. Once flexible working arrangements are in place, businesses should ensure employees (or other managers) notify them if there is any change – even a small change to working pattern or role can have knock on effects.

Using ESG performance metrics to drive cultural change

Once again, Covid-19 has demonstrated its ability to affect issues seemingly entirely removed from the auspices of a health crisis. In early October, Macfarlanes delivered a session to lawyers and industry representatives at the annual ProShare Conference titled "ESG and share plans - it's not all about the money". The tagline here refers to a trend in executive compensation that, while gaining traction over the past couple of years, has not yet attained the status of standard practice. The Coronavirus pandemic, with its track record of accelerating a range of global trends (such as developments in tech), may be about to change this.

Executive remuneration has traditionally been measured largely by reference to financial performance. Including "environmental, social and governance" factors in remuneration arrangements allows for the assessment of performance against metrics beyond the purely financial. For more on the specifics, please see our recent note. While the conversation around introducing such metrics into executive remuneration had moved comfortably out of the shadows in early 2020, the fallout of the pandemic has "sharpen[ed] the focus on the structural aspects of remuneration, particularly the question of excessive reliance on short term financial metrics" (as the ICGN recently noted).

In advance of the ProShare conference, the Macfarlanes remuneration team undertook some fieldwork to obtain a sample of current practices in this area, comprising a review of the remuneration reports of each of the FTSE 100 companies. The survey showed that 44 companies made no mention of ESG at all. Of the 56 that did, only some disclosed whether it had a tangible impact on remuneration; where this was the case, 23 companies had included it in their short-term bonus awards while only 4 did so in their long-term incentive plan (and eight had included it in both).

It is true that many ESG metrics are appropriate for inclusion in shorter term arrangements. But the reticence to include them in long term plans to date may have reflected a nervousness about the future of this trend. Now though, the increasingly apparent longevity of Covid-19 - and its attendant devastating social and economic impact - has highlighted a range of societal problems with such ferocity that companies may find it hard to ignore them.

Companies are therefore likely to want to demonstrate their commitment to tackling, for instance, the exacerbated health and safety concerns of their workers or issues with working conditions in their supply chain, by embedding it in their remuneration arrangements. The generalisation in scope here is not accidental - there is no reason that this should be limited to any particular sector or industry. Indeed one asset manager went so far as to predict earlier in the year that: "no compensation plan will be left unchanged by Covid-19.

If you would like to hear more about our survey or explore this topic in more detail, please do get in touch.

New prudential regime: time for investment managers to focus

On 23 June, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) published a discussion paper (DP) on the new prudential regime for investment firms ushered in through the EU’s Investment Firms Regulation (IFR) and Directive (IFD).

The IFR and IFD were finalised in December 2019. Although the EU implementation deadline is 26 June 2021, the FCA has confirmed that the new prudential regime will come into force in the UK on 1 January 2022.

The DP will be of interest to all investment managers authorised under the rules implementing MiFID and governed by the FCA’s BIPRU and IFPRU rules. It will also be relevant to those managers classified as Collective Portfolio Management Investment Firms (CPMIs) and those classified as exempt-CAD firms.

Those with investments or looking to invest in other managers or broker-dealers, including private equity and credit fund managers, will also be in scope. The provisions in the DP on groups will potentially impact holding companies of those firms directly, with discussion between HM Treasury, the Bank of England, the Prudential Regulatory Authority (PRA) and the FCA ongoing as to the imposition of requirements directly upon holding companies.

Purpose and relevance

In the DP, the FCA makes clear that the aim of the new prudential regime is to achieve similar intended outcomes as the IFR and IFD, such as simplified yet effective prudential requirements that ensure a level playing field across all investment firms while also taking into consideration the specifics of the UK market.

The DP is focused on ensuring the prudential regulation is fit for purpose with Chris Woollard, the interim Chief Executive of the FCA at the time, noting that the new regime is designed with investment firms in mind, replacing many rules that were largely designed for deposit-taking credit institutions. The FCA notes that new prudential rules in the UK would help it better deliver against its objectives and introduce significant improvement while lowering “ongoing regulatory costs”.

There is, however, no mention of the FCA’s objective to mitigate the ever-escalating costs of the Financial Services Compensation Scheme (FSCS) borne by well-run asset and investment management firms. The growing market concern that the prudential regime and the mutualisation system of the FSCS should be reformed to ensure the “polluter pays” was discussed in Charles Randall’s recent speech. It is unclear how much of this has fed into the FCA’s thinking on the IFR and IFD.

The final word on the application of the IFR and IFD in the UK?

Although the FCA formally states in the DP that the UK will not be implementing the IFD/IFR as it has now left the EU, it is clear from the DP that the FCA is in broad agreement with its policy objectives and intended outcomes, and of course, the FCA was heavily involved in the discussions on the new EU regime.

The FCA, however, takes care in the DP to reserve its position noting that the DP does “not necessarily reflect our final settled position on the correct interpretation of certain elements of the legislation.” Readers of the DP hoping to glean the extent to which the new UK regime might potentially deviate from the detail of IFD/IFR (or gain broader insight into the Brexit negotiations between UK/EU and the extent of our future alignment with EU rules) are likely to be disappointed.

However, the FCA is also clear that a considerable amount of detail remains outstanding in the new EU framework and it indicates that a consultation paper will be published “later in 2020” on the UK regime which will be known as the Investment Firms Prudential Regime (IFPR).

Remuneration changes

The IFPR also introduces significant changes to the current remuneration requirements for MiFID investment firms. The FCA confirms in the DP that the IFRPU (SYSC 19A) and BIPRU (SYSC 19C) remuneration codes will be deleted entirely and a new remuneration code for all investment firms in scope of the IFR/IFD will be introduced. Full scope AIFMs and UK UCITS management companies will however remain subject to their sectoral remuneration codes i.e. AIFM remuneration code (SYS19B) and UCITS remuneration code (SYSC 19E), respectively. The MiFID remuneration requirements in SYSC 19F would also continue to apply to all MiFID investment firms and to their staff.

The new remuneration rules will require many MiIFID investment firms to apply more onerous remuneration structure rules such as deferral, payment in non-cash instruments and performance adjustment which such firms have previously been able to avoid through proportionality or regulatory status. The current remuneration regime allows firms to apply certain rules “to the extent” that is appropriate, with the result that many UK asset management and wealth management firms currently disapply the more onerous remuneration structure rules mentioned above on grounds of proportionality. Since the IFD removes this wording, the FCA appears to interpret this to mean that MiFID investment firms will not be entitled to disapply such rules altogether, solely on the grounds of proportionality, because “instead proportionality is built into the IFD”. This may in due course prove unwelcome news for many firms and their material risk takers.

In addition to getting to grips with the remuneration rules, some MiFID investment firms will be required to establish a remuneration committee to oversee the review and execution of their remuneration policy, where they are not currently obliged to do so. Again, based upon the current regime, many firms disapply the remuneration committee requirement. The IFD also requires that remuneration committees must be “gender balanced” without defining this concept further. The FCA indicates that it interprets it as requiring “a culture of inclusion” and “appropriate representation” rather than prescribing an equal gender split.

Where can I get more information?

We have produced an interactive IFD/IFR tool for our clients to check the likely regulatory status of their firm under the IFPR and the key requirements that their firm will be in scope of applying once this regime comes into force on 1 January 2022. The tool will also take you to further detailed notes on the new remuneration requirements and what those mean for firms of different sizes. Please register your interest for the tool and get in touch if you would like to discuss any of these developments in more detail.

HMRC publishes research findings on tax-advantaged share schemes

Introduction

Tax-advantaged share schemes (TASS) have seen steadily increasing participation over recent years, in a push to improve employee engagement and ownership. Over 14,000 companies now offer a TASS to their employees (2018-2019).

HMRC commissioned the Social Research Institute at Ipsos Mori to conduct research into TASS with the aim of better understanding employer and employee perspectives towards the schemes and considering how to improve accessibility. The research explored the level of awareness and understanding of the schemes, and the motivations for and barriers to participation.

Findings

Both employers and employees were generally positive about TASS, reporting positive impacts on employee engagement and motivation, staff retention, and the ability to recruit competitively.

However, both cited a limited awareness of the schemes and an exact understanding of how they work as a significant barrier to participation. Of those employers who offer TASS, many outsource the management of the schemes to external advisers for this reason.

Further deterrents to participation include the costs and administrative burden of setting up and managing a scheme, as well as a lack of flexibility – specifically in terms of eligibility criteria, the length of the schemes, and financial limits.

Younger or more junior employees are particularly reticent to participate in TASS. They typically have less disposable income, less confidence when it comes to money management and investments, and a weaker sense of job security and long-term company loyalty. As a result, they tend to be more risk-averse than their senior counterparts.

Recommendations

Based on these findings, the report made several recommendations for improvement. These largely centred on shifting perceptions of TASS through education for both employers and employees and introducing a greater degree of flexibility to make the schemes more attractive – particularly to young employees and small businesses.

Please see the full report.

Employment tax and negative earnings

Introduction

The changes to bankers’ remuneration introduced by the then FSA around the time of the financial crisis and the subsequent introduction of rules such as deferral, clawback and malus, have created the concept that cash or shares can be paid or transferred by employees to employers.

As a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, there has been a renewed focus on negative earnings for a number of reasons including the following:

- directors and employees voluntarily handing earnings back to their employers to keep them afloat during the crisis, preserve their cashflow and avoid redundancies; and

- fixed or variable remuneration (whether cash or share-based) being forfeited by virtue of contractual clawback provisions being activated by a crisis-driven termination of employment or deterioration in the employer company’s financial results since the remuneration was paid or vested.

The question is then whether tax relief can be claimed on negative earnings.

The Martin case

In September 2014, the case of Martin v HMRC considered the concept of negative taxable earnings in relation to a contractual retention payment, which subsequently became repayable when the employee handed in his notice. The Upper Tribunal held the following:

- negative earnings from an employment in a tax year could reduce positive earnings from that employment in that year for income tax purposes, still leaving a positive amount of taxable earnings; and

- negative earnings from an employment in a tax year could exceed positive earnings from that employment in that year for income tax purposes, giving rise to the possibility of relief in respect of the excess.

The scope of negative earnings

Voluntarily handing back earnings

The Martin case would suggest that earnings voluntarily handed back to his employer would be capable of constituting negative earnings. This is because just as a discretionary bonus that the employer is not contractually obliged to make may constitute positive earnings, so a voluntary payment by an employee to the employer should, if made by reason of employment, be capable of constituting negative earnings. However, there is no authority on the point, as the specific point did not arise in the Martin case.

Employee share options

In the 2017 case of Sjumarken v HMRC, HMRC argued that the forfeiture of options could not constitute negative earnings because their acquisition did not constitute positive earnings. It was also argued that the options did not belong to the taxpayer to give up, as they had lapsed according to their terms as a result of the termination of his employment.

It would be difficult to argue that the lapse of an employee share option on a bad leaver termination constituted negative earnings, even if it involved significant value moving from the employee to the employer.

Malus and clawback

It would seem logical to conclude that a retransfer of shares triggered by a termination of employment as a bad leaver or by virtue of provisions implementing a remuneration code would constitute negative earnings, provided the forfeiture arises out of the employment. However, it should be noted that there is no authority on this as the Martin case involved a cash repayment, not a retransfer of shares.

The value of negative earnings

In terms of the value of the negative earnings, there is absolutely no authority on the point. However, applying the Martin case, there is much to be said for the argument that the value of the negative earnings is the value of the shares in the employer’s hands

This was first discussed in a Tax Journal article by Nigel Doran from the Macfarlanes tax and reward team, published in July 2020.

Preparing for changes to the IR35 legislation

The “IR35” legislation is changing from 6 April 2021. This article considers some of the common “off-payroll” scenarios that will affect the companies that engage consultants to provide services.

What is IR35?

IR35 legislation applies where an individual provides services to their client through an intermediary entity (generally a limited company known as a personal services company or PSC).

The rules reclassify payments made to that intermediary, where the relationship between the individual and their client is akin to an employment-type relationship. The reclassification of payments results in the individual effectively being subject to the same employment taxes as an employee of that client.

What changes from 6 April 2021, and who do the new rules apply to?

At present the PSC is required to determine whether a reclassification of payments is required.

As of 6 April 2021, clients that meet the criteria to be considered ‘medium or large’ are required to take “reasonable care” to make a determination of the tax status of the individual, issue a status determination statement (SDS) to the individual, and apply PAYE and NIC withholding where applicable.

A medium or large company is one that meets two of the following criteria: i) annual turnover of at least £10.2m, ii) balance sheet total of at least £5.1m, iii) more than 50 employees. Group companies must consider these criteria in aggregate across the group, to determine whether the new IR35 rules apply.

LLPs and overseas companies are within the scope of the rules (unless they are not UK resident and have no permanent establishment in the UK).

Where the new rules do not apply, the individual’s PSC remains responsible for making the determination and applying the original IR35 legislation.

Common scenarios

Scenario 1: A company has a non-executive director (NED) who provides services through their own limited company

The role of a NED is always classified as an “office holder”, and remuneration for services provided in this capacity should always be treated as employment income.

As of 6 April 2021, companies within the scope of the IR35 legislation will be required to:

- Issue an SDS to the NED, communicating the individual’s status as a “deemed employee” for tax purposes; and

- Operate PAYE and NICs withholding to payments made to the NED.

Note: it may be possible to adjust withholding if the NED is UK non-resident and performs some duties outside of the UK, or is outside of the scope of NIC.

Once employment taxes have been withheld from payments to the NED’s PSC, that individual may extract funds from their PSC without further tax charges.

Technically it is possible for a NED to provide consultancy services separate from the NED services, but this is an area of increased scrutiny for HMRC, and companies should ensure there is sufficient distinction between the services provided before taking this view.

Scenario 2: A company engages a senior individual who provides ad hoc investment advisory services

Determining whether the services provided by an individual are within the scope of the rules requires a review of the contractual engagement between parties, and the reality of the services provided. A few of the factors that require consideration include:

- Substitution – a genuine right of substitution is a strong indicator of self-employment. To be effective, the PSC must have the right to send any suitably qualified and experienced worker to perform the service, at the cost of the PSC. This is clearly not practical in many cases (for example senior individuals who provide contacts or expert advice).

- Control – if the client has control over what, where, how, and when a service is performed, it is a strong indicator that the worker is operating like an employee. Senior specialists may act with a greater degree of autonomy in this regard. If an individual is engaged to provide a specific task, and may complete that task however he or she wishes, it is clearly more like a self-employed relationship than a worker engaged on a monthly retainer, who is required to provide any services requested by a supervisor at the client.

- Mutuality of obligation – if the individual can turn down work at will, and there is no expectation that the client will provide paid work for the employee, then a mutuality of obligation may not exist – this is indicative of a self-employment type relationship. Factors that indicate the opposite include an overreaching contract for services, a fixed retainer fee, or a regular pattern of service that indicates an expectation.

- Financial risk – if the individual is taking on cost (e.g. other staff, the costs of expenses) to provide a service, this is an indicator of a genuine self-employment arrangement. A self-employed individual is generally paid for the provision of a specific service, rather than receiving a salary type payment based on time.

- Rights and integration – a self-employed worker should be excluded from employment-type rights including a workplace pension, holiday pay, etc. The worker should also not be ‘integrated’ within the business – ideally it should be possible to distinguish that worker from an employee (for example, no client email address, no access to employee benefits, no attendance to employee training or social events, no fixed office within the client’s offices etc.)

Even if the client determines that the individual does not need to be considered a “deemed employee” under IR35, an SDS should still be issued, and the arrangement should be reviewed (with reference to the above factors) if there is a change in contractual engagement or the way in which services are provided.

Scenario 3: A company uses an agency to provide IT support, various individuals are provided but before services are provided they must meet the firm security criteria

The agency rules are slightly different to the IR35 rules but require consideration of similar factors to those set out above. The first consideration is whether the agency is providing individuals to the company, or a service. An example of the former would be, “we will provide 3 individuals for 30 hours per week”, and the latter would be, “we will ensure your computer systems are fully functional and will deal with any errors”.

If a “service" is being provided by the agency, the company may have “fully contracted out” the services, and so do not need to consider the IR35 legislation further.

If individuals are provided, the company is required to consider the IR35 legislation (and factors listed in scenario 2) and issue the SDS’ to the agency providing the workers. In this case, the company would be advised to review the engagement it has with any agencies, to ensure they include the relevant indemnities etc., so that they are protected in the event they do recommend that the agency operates PAYE.

Next steps

With the changes five months away, we recommend that clients take the following steps we have laid out.

- Establish whether the business meets the criteria to be considered “medium or large”.

- Identify existing contractors and agency relationships, and review contracts and working practices to make status determinations ahead of the rule changes.

- Ensure all new engagements are “IR35 ready” – make up front status determinations on all new engagements.

- Communicate the status determinations to new and existing contractors.

The PRA and FCA consultation papers on amendments to their remuneration rules

On 31 July 2020, the PRA issued CP12/20 (the PRA consultation paper) amending the remuneration part of the PRA rulebook. Shortly after, on 3 August 2020, the FCA issued CP20/14 (the FCA consultation paper) amending its dual-regulated firms Remuneration Code (SYSC 19D) and relevant non-handbook guidance. The changes to the PRA and FCA remuneration rules, as set out in the consultation papers, are required as a result of the latest iteration of the EU’s Capital Requirements Directive (CRD V) which must be transposed into UK law by 28 December 2020. As the Brexit transition period will not have ended by that date, the UK is required to implement CRD V domestically.

The proposed changes to the remuneration rules set out in the consultation papers will be of interest to “class 1 firms” and “class 1 minus firms” (i.e. investment firms which have dealing on own account and/or underwriting/firm placing permissions but do not meet the €30bn asset threshold for Class 1 firms).

FCA-authorised investment firms (class 2 firms) will remain subject to the existing rules in the IFPRU Remuneration Code (SYSC 19A) or BIPRU Remuneration Code (SYSC 19B), as appropriate, until the new UK prudential regime for MiFID investment firms (the Investment Firms Prudential Regime (IFPR)) comes into effect in 1 January 2022. This new regime will replace the IFPRU and BIPRU Remuneration Codes with a new remuneration code that will be based on the Investment Firms Regulation and Directive (IFR/IFD). We have previously commented on the new investment firm regime in a separate article in this Autumn Update.

Overview of proposed changes to remuneration rules

The draft rules set out in the PRA’s CP 12/20 and the FCA’s CP 20/14 will affect both the firms and individuals that will be in scope of the remuneration rules and the way in which those rules apply.

In particular, the draft rules change the way in which proportionality applies to firms and individuals with the effect that more firms and individuals will become subject to some or all of the remuneration rules for the first time. The remuneration rules in CRD V are not materially different from the remuneration rules in the current CRD IV and so the Consultation Papers are not proposing radical changes to the substance of the remuneration rules.

Changes to proportionality

The current guidance on the application of proportionality allow firms with total assets below £15bn to disapply certain onerous remuneration structure rules, namely those requiring firms to subject variable pay to deferral, payment in retained shares or other instruments, performance adjustment (malus and clawback) and the maximum ratio between fixed and variable pay (typically referred to as the “bonus cap”).

The existing proportionality guidance will be replaced by a new proportionality regime prescribed by CRD V and which covers both firms and individuals.

Firm-level proportionality

Under CRD V, firms with total assets equal to or less than €5bn can disapply requirements relating to deferral, payment in retained share or other instruments and holding and retention periods for discretionary pension benefits. However, importantly, the application of firm-level proportionality does not allow firms to avoid subjecting variable pay to performance adjustment and the bonus cap where such variable pay is paid to “material risk takers” or “MRTs” (this concept is explained further below).

The €5bn asset threshold can be increased to €15bn by Member States - and the PRA and FCA propose to implement such an increase (which will be converted into a £13bn threshold under the proposed rules) - provided the relevant firm has:

- no obligations, or is subject to simplified obligations, for recovery and resolution planning purposes;

- a small trading book (i.e. traded business ≤ 5% total assets and < €5m); and

- traded derivatives positions ≤ 2% of its total on- and off-balance sheet assets, and the total value of its overall derivatives positions ≤ 5%.

Despite the proposed £13bn threshold being near the existing £15bn limit, it is important to note that the application of proportionality does not allow firms to disapply the rules relating to performance adjustment and the bonus cap. This means that a number of firms that have been able to avoid malus and clawback and the bonus cap will now have to apply such requirements for the first time.

Individual-level proportionality

Under existing rules, individuals whose variable pay is no more than 33% of total pay and whose total pay is no more than £500,000 (de minimis MRTs) can avoid the remuneration rules relating to deferral, payment in retained shares or other instruments, performance adjustment and the bonus cap.

Under the new proportionality rules relating to individuals, only individuals with variable pay equal to or less than €50,000 (will be converted to £44,000 under the proposed rules) and where such variable pay represents no more than one third of total pay are outside the scope of the remuneration rules. In addition to significantly lowering the threshold for de minimis MRTs, the new proportionality rules do not allow individuals to escape the rules on performance adjustment and the bonus cap which will apply to all MRTs.

Changes to remuneration rules

Deferral periods

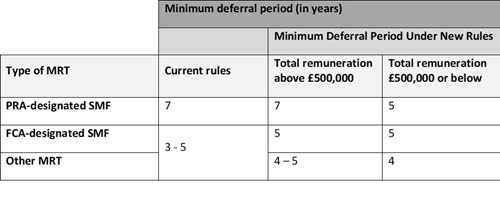

The PRA and FCA intend to amend the minimum deferral periods in current rules to align them with those in CRD V. Currently, MRTs that are not de minimis MRTs are subject to minimum deferral periods of 7 years (for MRTs who perform a PRA-designated senior management function (SMF)) and 3 to 5 years for all other MRTs. De minimis MRTs do not have to apply deferral.

As the minimum deferral period under CRD V is 4 years for MRTs that are not members of the management body and senior management of firms, the Consultation Papers provide a new, more nuanced, deferral framework for MRTs which takes into account both the type of MRT and the total remuneration received. The table below sets out an overview of the minimum deferral periods as set out in current rules and what these will look like once the new rules come into effect.

Clawback periods

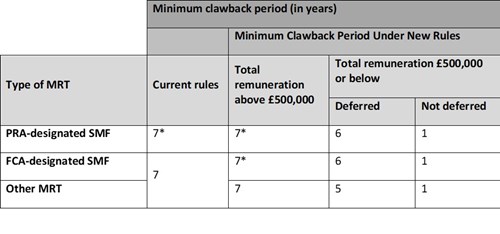

Although CRD V requires variable pay for MRTs to be subject to clawback, it does not prescribe the period during which clawback may be applied. Currently, the PRA and FCA require variable pay to be subject to clawback for a period of at least 7 years from the date of award (which may be extended to 10 years in certain circumstances). As this period applies from the date of award, it does not take into account the length of any deferral and retention periods (which in practice can mean particularly long clawback periods for variable pay which is not deferred).

Under the proposed new rules, the applicable clawback period will be determined by reference to the relevant deferral and retention periods (which in turn are determined by the type of MRT and total remuneration received as set out above). As with the new deferral period, this results in a more nuanced approach.

For MRTs who receive total remuneration of £500,000 or below and whose variable pay is not subject to deferral, the PRA and FCA are proposing a minimum clawback period of 1 year which is equal to the applicable retention period. The table below sets out an overview of the minimum clawback periods as set out in current rules and what these will look like once the new rules come into force.

*Minimum clawback periods may be extended to at least 10 years in certain circumstances

Payment in instruments

In line with CRD V, both regulators propose to permit firms whose shares are listed on a stock market to award variable pay in the form of share-linked instruments and equivalent non-cash instruments to satisfy the requirement that at least 50% of an MRT’s variable remuneration must be awarded in certain instruments. This aims to recognise that these instruments are as effective as shares in aligning the interests of the individual with those of the firm and that the use of such instruments can also achieve equivalent prudential benefits.

Identification of MRTs

CRD V updates the basis for identifying certain categories of MRTs, specifying certain categories of staff whose professional activities have a material impact on the firm’s risk profile. The PRA and FCA therefore propose to replicate CRD V’s revised approach to identifying MRTs in the updated PRA Rulebook and Dual-regulated firms Remuneration Code. CRD V’s revised approach will also extend to MRTs in subsidiaries of third-country firms that are established in the UK.

The relevant rules will also refer to the EBA’s final draft regulatory technical standards (RTS) where certain terms and definitions are set out.

Next steps

The consultation closed on 30 September. In scope firms are required to apply the revised remuneration requirements to any remuneration awarded in relation to the first performance year starting after 29 December 2020. For remuneration awarded on or after 29 December 2020 in respect of earlier performance years, firms should continue to apply the existing rules.

Get in touch

Related content

See all related content