Corporate Law Update: 21 - 27 August 2021

27 August 2021In this week’s update: An ILPA consultation on changes to its standardised due diligence questionnaire, the “Managing Director” of a business division was not in fact a company director, an investor did not lose its right of claim against a third party by virtue of investing indirectly through a company, ISS publishes guidance on steps companies can take in relation to climate change and the CMA responds to the Government’s consultation on audit reform.

- The ILPA is seeking views on proposed changes to its standardised due diligence questionnaire and diversity metrics template

- The “Managing Director” of a business division was not in fact a company director

- An investor did not lose its right of claim against a third party by virtue of investing indirectly through a company

- ISS Corporate Solutions publishes guidance on steps companies can take in relation to climate change

- The CMA publishes its response to the Government’s consultation on audit reform

ILPA seeks comments on revised due diligence questionnaire and diversity metrics template

The Institutional Limited Partners Association (ILPA) has invited comment on a revised version of its standardised due diligence questionnaire (DDQ).

The ILPA is a trade association for institutional limited partners in the private equity asset class. It claims more than 5,000 professional members across over 50 countries, managing 50% of the global institutional private equity assets under management (AUM). Members include pension funds, endowments, foundations, family offices, insurance companies, investment companies, development financial institutions and sovereign wealth funds.

Limited partners (LPs) proposing to invest in a fund will invariably conduct due diligence on the fund and sponsor before investing. In part, this will involve the LP sending a DDQ to the fund, asking for information and confirmations in various areas.

The ILPA’s standardised DDQ is designed to promote consistency between different LPs’ DDQs and, as a result, to generate efficiencies and to reduce the administrative burden on LPs, general partners (GPs), placement agents and other interested parties.

Key proposed changes to the standardised DDQ include the following.

- New sections covering succession planning and key persons, co-investments, GP-led secondaries and continuation funds, credit facilities, and data security and technology.

- An updated environmental, social and governance (ESG) section drawing on an updated version of the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) Limited Partners Private Equity Responsible Investment DDQ.

- A significant number of new and modified questions relating to diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), including in relation to metrics tracking, diversity policy, codes of conduct for harassment and discrimination, policies for recruiting in under-represented groups, and individuals’ contributions towards DEI.

- New questions relating to the fund’s values, culture and organisational goals, PPP loans and governmental assistance, as well as on opportunity pipelines.

- New questions on special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs).

- New questions on recruitment, retention, remote working, performance appraisals, training, internal controls, GDPR, political contributions, lobbying and whistleblowing.

- New questions on waterfall, preferred return hurdles, carried interest on gains gross of management fees and expenses, clawback of gross taxes paid, management fee calculation, and carried interest calculation and verification.

- New questions relating to valuation, audit and reporting.

In addition, the ILPA is seeking views on a revised version of its diversity metrics template, which serves as a model for presenting gender and ethnicity breakdowns for management companies, investment committees and portfolio company boards.

The ILPA has asked for comments by 24 September 2021.

“Managing director” was not in fact a director

The High Court has held that a person who styled himself the “Managing Director” of a business division but had not been formally appointed as a director was not a “de facto director”.

What happened?

Bishopsgate Contracting Solutions Ltd v O’Sullivan [2021] EWHC 2103 (QB) concerned a group of companies operating in the construction sector.

Mr O’Sullivan was employed by a company (MSSL) within the Munnelly Group, which was ultimately controlled by a Mr Munnelly.

In 2012, Mr O’Sullivan was involved in developing a new group of companies – the “Bishopsgate Group” – which was to operate alongside the Munnelly Group but remain operationally distinct from it. Mr O’Sullivan was never formally appointed as a director of any of the companies in the Bishopsgate Group. However, he was heavily involved in the new group’s work and eventually came to describe himself, both internally and to third parties, as the group’s “Managing Director”.

In late 2016, Mr O’Sullivan authorised the provision of credit by a company within the Bishopsgate Group (which we will call BCSL) to a client and allowed it to grow to almost £600,000. That client subsequently entered administration and BCSL had to write off almost £500,000 of the amount. This was despite alleged instructions from Mr Munnelly not to extend credit.

BCSL brought proceedings against Mr O’Sullivan, claiming that, although not formally appointed as a director, by virtue of his actions he had become a de facto director and that, by extending credit without authority, he breached his duties to BCSL under sections 172 and 174 of the Companies Act 2006.

To establish that Mr O’Sullivan had breached these duties, BCSL needed to persuade the court that he was a de facto director. (BCSL did not argue that Mr O’Sullivan was a shadow director.)

English law recognises three different types of company director.

A de jure director (“director in law”) is someone who has been formally and validly appointed or re-appointed (normally by the company’s board or shareholders) to perform the office of director of a company. Most company directors are de jure directors and their details appear at Companies House.

A de facto director (“director in fact”) is someone who has not been formally appointed as a director, often (but not always) because of some defect in the appointment process, but nonetheless carries out the functions and responsibilities of a director (even if they do not describe themselves as such). There is no single test for identifying a de facto director, but a person will not be a de facto director merely because they carry out senior or executive functions. Rather, they must be part of the company’s “corporate governance structure” and carry out functions that only a director can perform.

A shadow director is someone who neither has been formally appointed as a director nor carries out the roles or functions of a director, but in accordance with whose directions or instructions the company’s board is accustomed to act. Effectively, a shadow director is someone who controls the board from behind the scenes.

In theory, a person can be both a de facto director and a shadow director at the same time, although this is very unusual. The statutory duties that come with serving as a director apply to all three categories (although they do not apply at all times to shadow directors).

(Other variations of directorship exist in practice, including executive directors, non-executive directors, professional or nominee directors, and alternate directors, but, in each case, a director of these kinds will fall into one of the categories above.)

BCSL claimed that Mr O’Sullivan must have been a de facto director because, among other things:

- he set up and ran the Bishopsgate Group of companies for four years;

- he appointed and described himself, both to the internal workforce and to third parties. as the “Managing Director”; and

- it was he who implemented significant decisions actions, including hiring personnel, finding clients, deciding the terms on which BCSL did business and extending credit to third parties.

What did the court say?

The court said that Mr O’Sullivan was not a de facto director. The judge gave the following reasons.

- Although established as a separate group, the Bishopsgate Group was effectively run as a division of the Munnelly Group. Mr Munnelly himself described Mr O’Sullivan as the “head of a department of business conducted and operated by Mr Munnelly”.

- As a result, there was no corporate governance structure specific to BCSL or any other Bishopsgate Group company. No board meetings took place – only “senior management meetings” involving Mr Munnelly, Mr O’Sullivan and managers within the Munnelly Group.

- Mr Munnelly had the right to tell Mr O’Sullivan what to do and to veto decisions. In particular, Mr Munnelly insisted that Mr O’Sullivan had no authority to extend credit on behalf of BCSL without his authorisation. In effect, Mr O’Sullivan was managing BCSL’s day-to-day business (including extending credit) under the authority of, and within the limits set by, Mr Munnelly.

- Everything Mr O’Sullivan did was done under his contract of employment with MSSL and was capable of being done by a senior manager reporting to Mr Munnelly.

- Although Mr O’Sullivan described himself as “Managing Director”, he did not attribute this role to any particular company. If anything, he had described himself as the managing director of the Bishopsgate business. This title accurately reflected his role as a senior manager within MSSL.

- All documents with third parties required the signature of BCSL’s only de jure director, a Mr Sexton. The fact that Mr Sexton was required to sign documents, rather than Mr O’Sullivan, would have led third parties to the conclusion that Mr O’Sullivan was not a director of BCSL.

Having decided that Mr O’Sullivan was not a de facto director, the court concluded that the duties in sections 172 and 174 did not apply to him.

What does this mean for me?

Ultimately, this decision boiled down to a question of control. Although Mr O’Sullivan was central to a range of managerial functions within the company in question, he was not ultimately responsible for taking decisions and, to the extent he did, it was under authority delegated to him by Mr Munnelly.

The judge’s readiness to disregard Mr O’Sullivan’s adopted title was fortunate for him. When deciding whether someone is a de facto director, a court will focus more on a person’s day-to-day activities than on their title. But the way in which a person holds themselves out is important when deciding what functions they have assumed; on another day, this could have worked against Mr O’Sullivan.

It is never desirable for a company to have de facto directors, as this increases uncertainty over the entity’s corporate structure and muddies reporting lines and authorities. The case gives rise to some useful practical tips for avoiding the risk of a company having a de facto director.

- Create and follow a clear corporate governance structure. Ensure the company has directors who have been formally appointed and registered at Companies House. Make sure that decisions are taken at board meetings by these directors and the decisions are minuted.

- Delineate clearly any delegated authorities. Generally, significant contracts and documentation should be signed by a company’s directors. If anyone other than a director is to be given authority to sign documents or negotiate transactions, set this authority out specifically in writing.

- Consider retaining someone under a formal contract of employment. It is common for a person acting as a director to be employed in parallel under a contract of employment. However, it is less likely that a person who has not been formally appointed will be considered a de facto director if they are an employee and carrying out functions that an employee could carry out.

- Choose job titles carefully. Clearly assigning a job title that does not include the word “director” will reduce the risk that a person will be found to be a de facto director (although it will not eliminate it). If individuals are to be styled “director” despite not being statutory directors, take care to ensure, when necessary, that third parties understand that the person is not a statutory director.

Investor did not lose right of claim when investing indirectly through a company

The Privy Council has held that an investor in a fund did not lose its right to claim against the administrator and custodian by virtue of the so-called “rule against reflective loss” when it exchanged its direct holdings for shares in an intermediate company.

What happened?

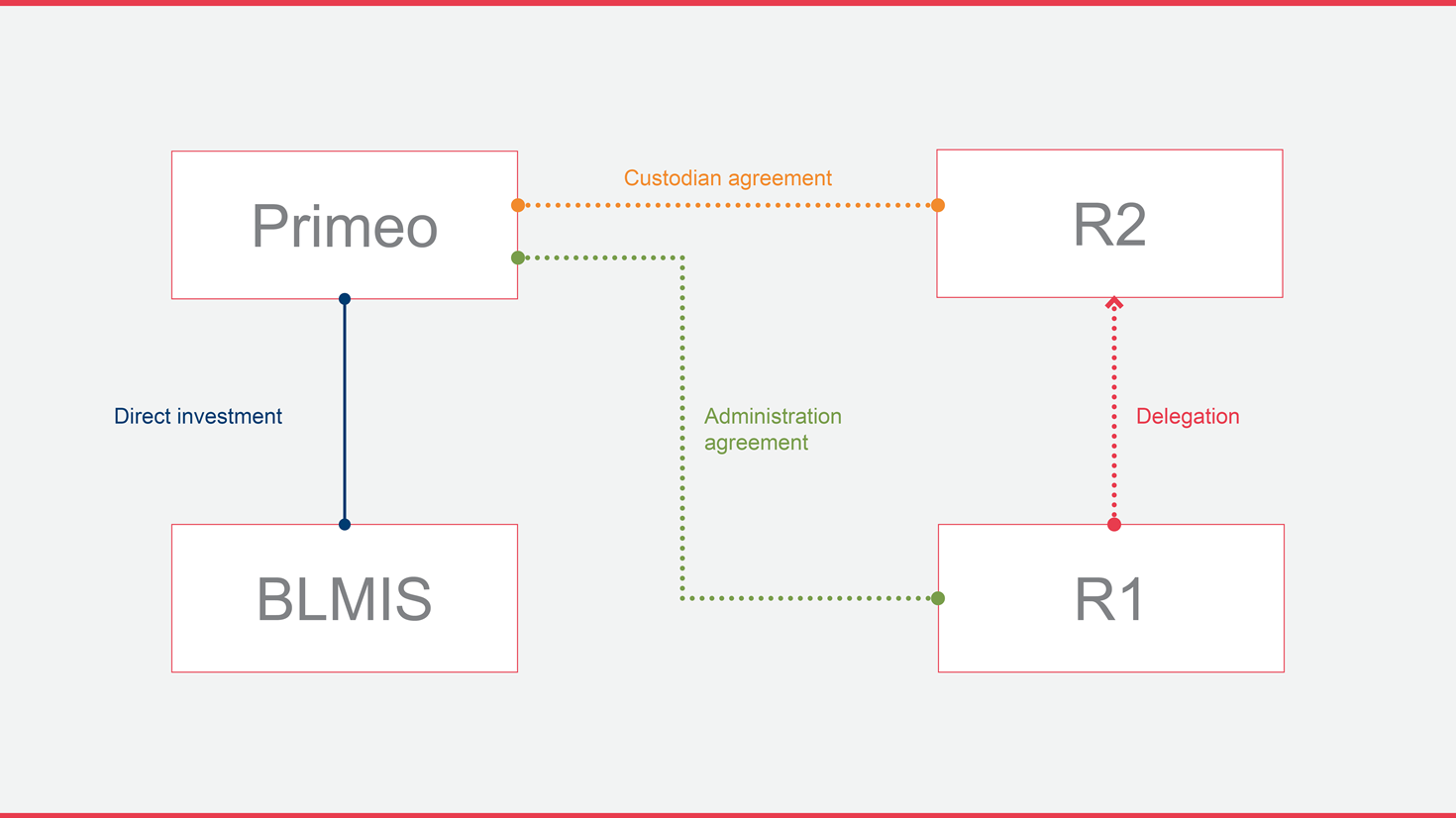

Primeo Fund (in liquidation) v Bank of Bermuda (Cayman) Ltd [2021] UKPC 22 concerned a Cayman Islands company – “Primeo” – which had carried on business as an open-ended investment fund.

Primeo’s main purpose was to provide investors with access to the US equity markets. For this purpose, Primeo appointed a custodian (R2) and an administrator (R1). R1 delegated most of its duties to R2, so, in practice, R2 acted as both custodian and administrator.

At the outset, Primeo placed a proportion of its funds with Bernard L Madoff Investment Securities LLC (BLMIS), which turned out to be the vehicle by which Bernard Madoff conducted his Ponzi scheme.

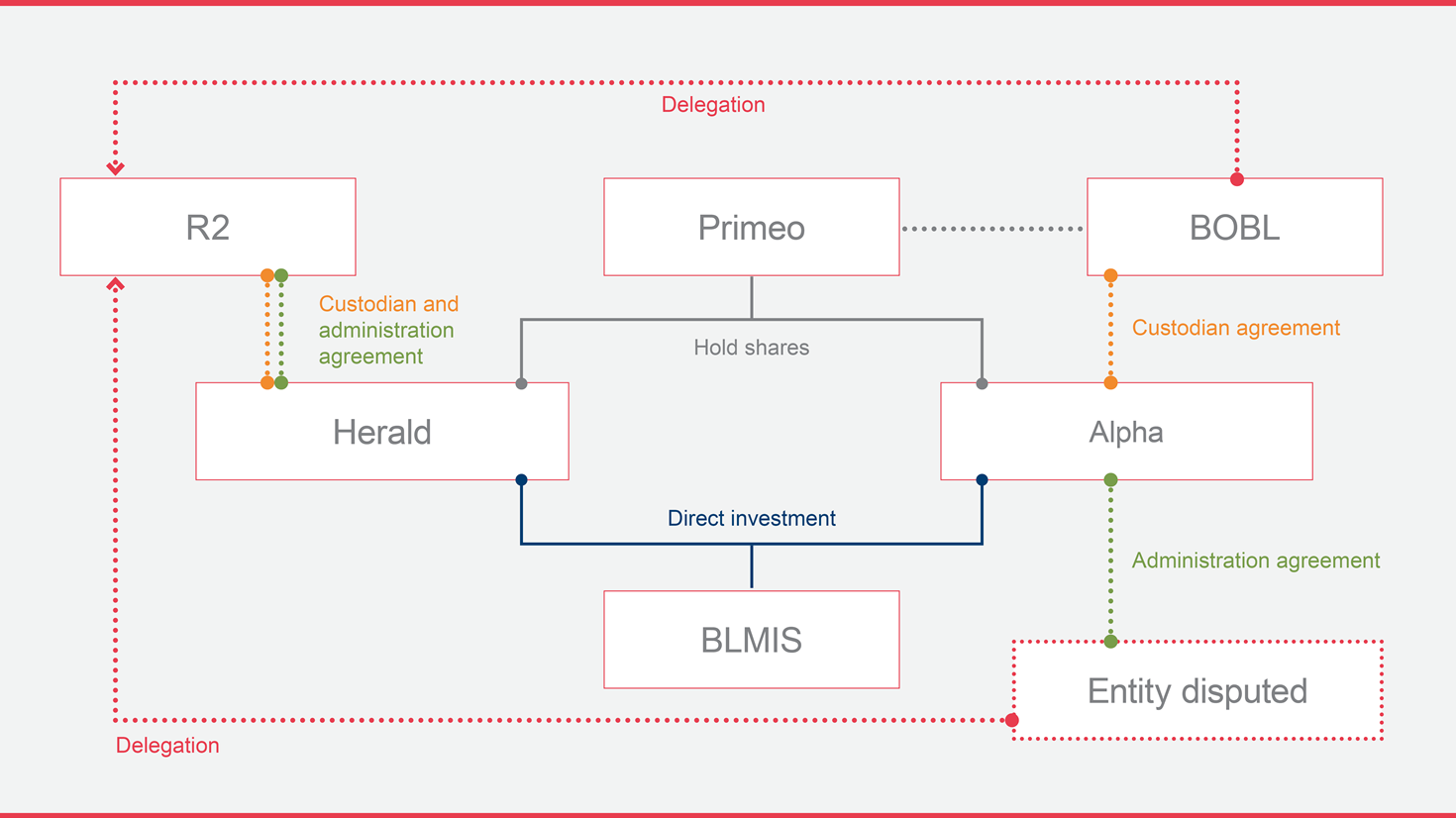

Over time, Primeo increased its investment in BLMIS, both by investing directly and by investing indirectly through two feeder funds: “Herald” and “Alpha”. Whenever Primeo invested through Herald or Alpha, it received shares in that feeder. Herald and Alpha in turn invested all their assets in BLMIS.

Herald employed R2 as its custodian and administrator. Alpha employed Bank of Bermuda Limited (BOBL) as its custodian, which in turn appointed R2 as sub-custodian. It was not clear who Alpha’s administrator was but, in practice, R2 also acted as its sub-administrator. Alpha had no contractual relationship with R2, and neither Herald nor Alpha had any contractual relationship with R1.

By April 2007, 100% of Primeo’s assets were invested in BLMIS, with around 10% of its investment held indirectly through Herald and Alpha.

In May 2007, Primeo restructured its investment in BLMIS by transferring its direct investments to Herald in exchange for further shares in Herald. From that point, Primeo held only indirect investments in BLMIS – 97.5% through Herald and 2.5% through Alpha.

The Ponzi scheme operated by BLMIS collapsed in December 2008, causing the entire net valuation of Primeo’s assets to fall through. Primeo was placed into liquidation in January 2009.

Primeo’s liquidators brought proceedings against R1 and R2. They claimed that, if R1 and R2 had performed their duties properly as administrator and custodian, then:

- Primeo would not have continued to place funds directly with BLMIS and would have redeemed the direct investments it had already made; and

- it would not have continued to place funds indirectly through Herald and Alpha and would have recouped its indirect investments by redeeming its shares in Herald and Alpha.

In response, R1 and R2 argued that the rule against reflective loss (see box below) prevented Primeo from claiming against them, because Primeo was a shareholder of Herald and Alpha and its loss merely represented any loss that Herald and Alpha had suffered by virtue of R1’s and R2’s actions.

It is a fundamental tenet of English law that a company is a legal person separate from its shareholders, and that, where a company and its shareholders suffer a wrong, each of them is entitled to bring their own claim. However, this is modified by the “rule against reflective loss”.

This rule (also known as the “rule in Prudential”) applies where both a shareholder of a company and the company itself have suffered loss and so both have a claim against the same third party (the “common wrongdoer”) in respect of the same wrongdoing.

In those circumstances, the shareholder is not permitted to claim for any diminution of the value of its shareholding in the company, or for any loss of distributions (e.g. dividends), which is “merely the result of a loss suffered by the company” and caused by that third party – so-called “reflective loss”. Instead, the right to claim damages lies with the company itself.

In Sevilleja v Marex Financial Ltd [2020] UKSC 31 (“Marex”), on which we reported previously, the Supreme Court confirmed that this is a substantive rule of law and not merely a procedural device to prevent double recovery. This means that the shareholder cannot claim for reflective loss even if the company itself declines to claim, potentially leaving the shareholder completely uncompensated. This is because, by taking shares, the shareholder has chosen to “follow the fortunes” of the company.

The rule does not prevent a shareholder from recovering loss in other circumstances, such as where the shareholder has their own personal claim.

Primeo counter-argued that its loss had arisen prior to, and independently of, its acquisition of shares in Herald and Alpha and that the rule did not therefore apply.

The Privy Council had to address several issues, but the three of most interest are as follows.

- At what point in time should the court ask whether the rule against reflective loss applies? Primeo argued that it was when the cause of action arises, which, in this case, was before Primeo had acquired shares in Herald and Alpha, meaning the rule could not apply. R1 and R2 argued that it was when legal proceedings were commenced, which, in this case, occurred after Primeo had become a shareholder in Herald and Alpha, thus engaging the rule.

- Was the rule triggered when Primeo transferred its direct investments to Herald? If so, Primeo would be unable to claim against R1 and R2, as it would have surrendered its claims when it acquired shares in Herald.

- Does the rule apply if the company and shareholder have claims against different people? The rule applies where a shareholder and company have claims against a “common wrongdoer”, but here there were mismatches (see section below). However, R1 argued that the rule applies whenever two claims compete with each other, even if they are made against different people.

At what point in time did the rule apply?

The Privy Council said that, when deciding whether the rule applies, the courts must look at when the right of claim arose, not when proceedings were commenced.

Primeo’s claims had arisen before it invested indirectly through Herald and Alpha. Each time Primeo placed a direct investment and BLMIS misappropriate the funds, Primeo “suffered an immediate loss”, giving rise to an immediate cause of action against R1 and R2.

Primeo suffered that loss in its personal capacity and not as a shareholder of Herald or Alpha. It had not chosen at that point to “follow the fortunes” of Herald or Alpha, and neither Herald nor Alpha had suffered any wrong committed by R1 or R2. There was “no sound logic” to apply the rule.

This did not change when Primeo started making parallel indirect investments through Herald and Alpha. Those investments were “completely separate” from Primeo’s direct investments.

Was the rule “activated” when Primeo restructured its investments?

No. Primeo’s right of action did not disappear when it became a shareholder in Herald.

- Although Primeo’s investments were ultimately represented purely by shareholdings in Herald (and Alpha), the loss it suffered was neither a consequence of harm done to Herald nor reflected by a diminution of the value of its shares in Herald. Herald might acquire its own claims which, if successful, might compensate Primeo by uplifting the value of the shares in Herald, but the losses suffered by Herald were distinct from those suffered by Primeo.

- As noted above, Primeo had not chosen to “follow the fortunes” of Herald in relation to the direct investments it had already made. By hiving its direct investments into Herald, Primeo was not choosing to subject them retrospectively to Herald’s prospects. In the Privy Council’s words, the “follow the fortunes” bargain was forward-looking, not backward-looking.

- When it exchanged its direct investments for shares in Herald, Primeo did not agree to forego any rights of claim it might have against R1 and R2. Clear words were needed to strip these rights away. A person does not, simply by acquiring shares in a company, automatically give up all rights of claim in relation to someone against whom the company also has a claim.

Did the rule apply where there was no “common wrongdoer”?

This rather ingenious argument succeeded before the Cayman Islands Court of Appeal.

Because Herald had employed only R2, it had no claim against R1. In relation to Primeo’s claim against R1, therefore, there was no “common wrongdoer”. However, R1 successfully argued that, because R1 had delegated its duties to R2, if Primeo recovered from R1, R1 would subsequently claim against R2, and this claim would compete with Herald’s claim against R2.

Likewise, Alpha had no claim against R2 and so, in relation to Primeo’s claim against R2, there was no “common wrongdoer”. However, R2 successfully argued that, because R2 was in practice acting as sub-administrator, if Alpha recovered from its contractual administrator (whoever that was), that administrator would simply claim against R2, thus competing with Primeo’s claim against R2.

The Court of Appeal agreed and said the rule against reflective loss applied in these circumstances, taking a “substance over form” approach.

The Privy Council, however, disagreed. It said that the rule was a limited principle that depended on there being an actual common wrongdoer. To apply it in the way the Court of Appeal had would be a “significant extension of the rule” and was undesirable for three main reasons.

- It ignored the separate personality of R1, R2 and Alpha’s administrator.

- Courts cannot simply assume that a contractor will automatically claim against its sub-contractor. It was not certain, for example, that R1 or Alpha’s administrator would claim against R2.

- By becoming a shareholder in Herald and Alpha, Primeo did not agree to “follow the fortunes” of those companies not only against their own contractual counterparties, but also as regards “onwards claims” that those counterparties might bring and the speculative impact of those claims.

What does this mean for me?

The rule against reflective loss is complicated and, whilst the decision in Marex clarified the rule itself, it has made it difficult in some cases to determine whether it applies.

The judgment gives rise to the following practical points, all of which a shareholder who is considering bringing a claim should discuss with its legal advisers. However, there are often instances where both an investor in a company and the company itself will have parallel claims against the same person. In these cases, it is important to consider whether the investor is barred from claiming.

- Is the shareholder seeking to recover a drop in the value of its shares? If so, it will be important to examine whether the loss is merely “reflective”.

- Did the shareholder’s cause of action arise before becoming a shareholder? If so, the shareholder will most likely have their own personal right of claim and the rule will not apply.

- If not, does the shareholder’s loss arise in consequence of a loss to the company? If so, it is likely to be unrecoverable, even if it exceeds the loss suffered by the company. However, in some cases, the shareholder’s loss may be totally distinct from any loss suffered by the company (and so recoverable), even if the loss is caused by the same person.

- If the loss is merely “reflective”, are there any other options open to the shareholder? Does it have any power to require the company’s directors to take action against a third party? If they refuse to do so or they settle for too low an amount, can the shareholder bring a derivative claim on behalf of the company against its directors for breach of their duty to the company, or even a personal claim for unfair prejudice?

- If none of that helps, does the shareholder have any alternative rights of claim against the third party that would not be barred as reflective loss? For example, does the shareholder have the benefit of a separate indemnity or covenant to pay, which could be enforceable as a debt?

Other items

- ISS publishes report on taking climate action. ISS Corporate Solutions has published a bulletin on the case for companies taking climate action. The bulletin, which is available on providing details to ISS, sets out actions a company can take now to assess and address its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. In particular, the bulletin contains a helpful “climate action toolbelt” comprising five steps, from calculating GHG emissions to setting reduction goals.

- CMA responds to Government consultation on audit reform. The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has published its response to the Government’s March 2021 consultation on reforms to company audit and corporate governance (see our previous Corporate Law Update). The CMA’s response focusses on the proposed audit reforms, with the CMA broadly supporting the Government’s proposals but recommending more challenging measures in relation to “shared audits”.

Get in touch