The war on holding companies and the return of withholding taxes

12 October 2021The proposals to be introduced by BEPS 2.0 and ATAD 3 represent the latest challenge to the use of holding companies in corporate structures, with BEPS 2.0 potentially giving rise to the re-introduction of withholding taxes where they had historically been falling away, and ATAD 3 bringing in prescriptive substance requirements.

These latest developments in the story of holding company anti-abuse measures will require corporate groups to review their holding structures and make changes if those structures could be affected by current trends or the proposed new measures.

A brief history

Intermediate holding companies are a common feature of international groups, often used to hold shares in subsidiaries organised on a regional or divisional basis. In a private equity context, holding companies are often used as the vehicle for investing in portfolio companies rather than holding interests directly through a fund partnership.

Once upon a time, it was not particularly controversial that holding companies were entitled to the benefits of tax treaties and (in the case of EU companies) directives in their country of residence. This would often restrict the right of investee jurisdictions to tax dividends and gains derived by the holding company from its local subsidiaries.

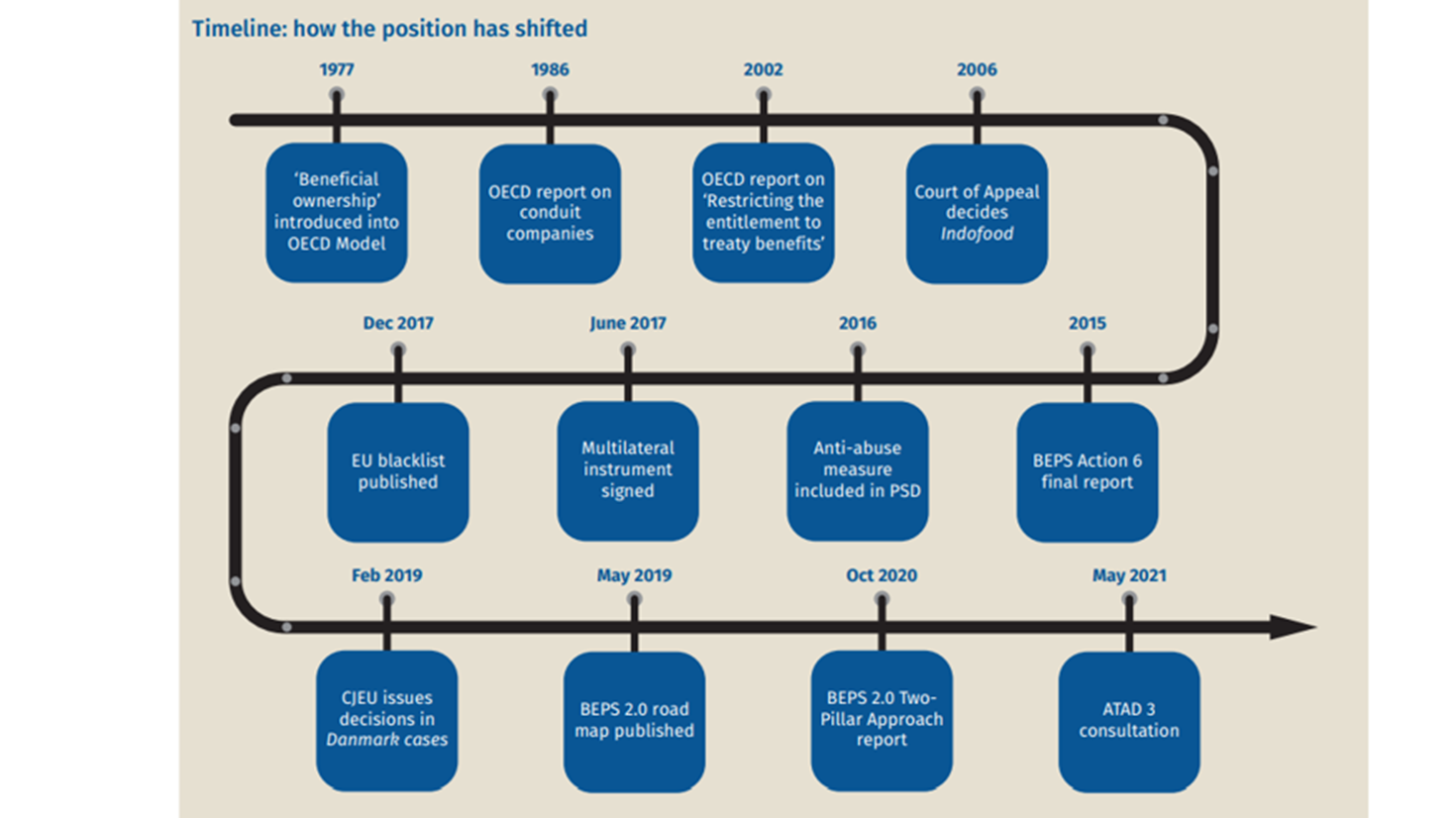

As our timeline shows, the position has shifted materially in recent years, with an accumulation of measures that can restrict access to the benefits of treaties and directives. Whilst this has a long history, going back to changes to the OECD model treaty in the 1970s, the challenge to the treaty status of holding companies began in earnest in 2015, when the OECD BEPS project recommended measures to restrict inappropriate use of tax treaties. This has subsequently gained momentum with a range of institutions (the EU, OECD, CJEU and individual tax authorities) setting a higher and higher bar that holding companies will need to meet in order to benefit from relief from withholding taxes and exemptions to non-resident capital gains tax.

The high watermark for this approach is the current EU public consultation titled Tax avoidance: fighting the use of shell entities and arrangements for tax purposes. Some of the questions in this consultation could be read as suggesting that it may never be appropriate for an intermediate holding company (using the term "shell entity") to benefit from reductions in withholding taxes under tax treaties and EU directives.

Beneficial ownership from the OECD to Indofood

To go back to the beginning, the story starts with the introduction of "beneficial ownership" into the OECD’s Model Tax Convention in 1977. In a withholding tax context, it asked: who actually benefits from the receipt of this payment? The term now appears in most double tax treaties and seeks to prevent treaty shopping by ensuring that the benefits of the dividends, interest and royalties articles are available only to residents of the contracting state that are the beneficial owners of the relevant payment.

In 1986, the OECD’s report on the use of conduit companies concluded that a conduit company cannot normally be regarded as a beneficial owner of a payment if, in practice, it is a mere fiduciary or administrator. The OECD wanted to prevent groups setting up shell or conduit companies to take advantage of a reduced withholding tax rate.

Despite these developments, there was no generally agreed definition of "beneficial ownership" in double tax treaties and the interpretation in any particular treaty would need to take account of the domestic law of the contracting states.

The case of Indofood International Finance Ltd v JP Morgan Chase Bank NA [2006] EWCA Civ 158 contains comments from the Court of Appeal suggesting that beneficial ownership could have an "international fiscal meaning" and was generally understood to be ascertained as a matter of legal construction. In the case, an intermediate company that had an obligation in commercial and practical terms to on-pay its interest receipts could not be the beneficial owner of that income (applying this "international fiscal meaning" in the context of a contractual dispute).

To avoid falling foul of this beneficial ownership test, some groups reviewed their holding structures and looked to eliminate fully back-to-back financing arrangements. Alternatively, some structures that involved payment chains were set up with an "equity gap" (i.e. an equity-funded company interposed between two debt-funded companies). These types of structural solutions reflected a widely held view that beneficial ownership was an objective test that was indifferent to the motives behind holding company arrangements.

Principal purpose from BEPS to Danmark

Action 6 of the OECD BEPS project sought to prevent the granting of treaty benefits in "inappropriate circumstances" and introduced new questions around subjective intent. The resulting multilateral instrument inserted minimum standards into the double tax treaties of its signatories to deal with treaty shopping: a principal purpose test (PPT), a limitation on benefits test (LOB), or a combination of the two.

Under the PPT, the benefit of a treaty would be denied if obtaining it was one of the principal purposes of the arrangement, unless granting the benefit in the circumstances would be in accordance with the object and purpose of the treaty. In its 2017 Model Tax Convention commentary, the OECD set out several examples that would not fall foul of the PPT.

One example features a regional investment platform that employs a local team of managers and performs various functions. The jurisdiction is chosen for a number of reasons: the availability of knowledgeable directors, a skilled workforce, membership of a regional grouping, and an extensive treaty network. Considering a jurisdiction’s treaty network as part of wider considerations is therefore not sufficient to trigger the PPT; this gave particular comfort to investment management groups with a significant presence in jurisdictions such as Luxembourg, as it focused on entities having sufficient people and economic substance in the relevant jurisdiction.

Another example demonstrated that treaty access being a deciding factor when choosing between jurisdictions that were equally commercially viable would not be caught on the basis that the PPT should not prevent genuine cross-border investment.

In contrast to the objective beneficial ownership test that preceded it (and the more mechanical LOB tests used in US treaties), the PPT introduced a subjective motive test into double tax treaties.

Danmark

The CJEU decisions of February 2019 in N Luxembourg 1 (Case C-115/16), X Denmark A/S (Case C-118/16), C Danmark I (Case C-119/16), Z Denmark ApS v Skatteministeriet (Case C-299/16) and Skatteministeriet v T Danmark (Case C-116/16), Y Denmark Aps (Case C- 117/16) (Danmark) concerned the interpretation of the EU Parent-Subsidiary Directive and the EU Interest and Royalties Directive (the EU Directives). However, certain tax authorities have applied the decision more widely to interpreting their double tax treaties.

In Danmark, the CJEU decided that national tax authorities should refuse to apply the EU Directives – meaning that domestic withholding taxes will apply – where the recipient of the payment is a conduit company. This is based on the principle that EU law rights cannot be relied upon for abusive or fraudulent ends.

Previous decisions such as in Cadbury Schweppes plc and Cadbury Schweppes Overseas Ltd v Commrs of Inland Revenue (Case C-196/04) suggested that a tax-motivated reason for a structure would not prevent a taxpayer from exercising an EU law right or freedom except in relatively limited circumstances where the resulting structure is wholly artificial.

The CJEU in Danmark, however, appeared to take a broader interpretation, placing greater emphasis on the purpose of the taxpayer in adopting a particular structure, including a focus on both physical presence in a jurisdiction, and whether the holding companies had proper economic enjoyment of the income they received.

The Danmark decision amalgamated several concepts in the context of applying EU anti-abuse provisions – beneficial ownership, conduit companies, principal purpose, and substance – in a sense, bringing together as a single doctrine all of the concepts discussed above in order to provide national tax authorities with the means to defeat claims for relief from withholding taxes made by foreign holding companies.

The war on holding companies

In more recent developments, the European Commission (EC) has published a consultation with a view to bringing in a directive in Q1 2022 (to be known as the third anti-tax avoidance directive, ATAD 3). The aim: to fight the use of "shell entities" and arrangements for tax purposes in the EU.

If "shell entity" is a synonym for "intermediate holding company", ATAD 3 may be more of an existential threat to European holding companies than anything that has come before it.

ATAD 3 reflects action previously taken by the EU to introduce rules regarding economic substance for its "blacklist" of non-cooperative tax jurisdictions. The EC is focused on situations where the ultimate objective is to minimise overall tax via the use of legal entities with no or minimum substance and no real economic activities.

Under current proposals, ATAD 3 will define substance requirements for EU entities, focusing on levels of employees, premises, functions performed, and risks undertaken to understand whether there is real economic activity in a jurisdiction. No examples are provided but holding companies with passive income appear to be the main target. As the proposals develop, ATAD 3 may clarify, or materially shift, the definition of what is an acceptable minimum level of substance for holding companies.

For entities that fail to meet these new standards, possible counteraction measures range from public disclosure of information about the shell entity and monetary sanctions, to denial of double tax relief, treaty benefits, or deductibility of costs, which will affect not just the entity in question but also the wider group.

The EC says the legislation will set out "indicators" of shell entities to be targeted. These may include:

- use of trust and company service providers;

- lack of own premises;

- passive income as main source (rent, interest, dividends, royalties);

- mostly foreign sourced turnover;

- low number of employees;

- lack of own bank account;

- outsourcing of income generating activities; and

- majority of non-resident directors.

The role played by a company is not taken into account; no distinction is made, for example, between holding companies and letterbox companies. In addition, it is unclear whether particular weight will be given to certain indicators over others. However, in practice the impact of ATAD 3 may be felt across a range of entities in international corporate groups, including:

- group holding companies in low-tax jurisdictions;

- investment holding companies established in jurisdictions with access to extensive treaty networks and the EU Directives (such as the Netherlands and Luxembourg); and

- group IP or treasury companies set up in EU countries with favourable tax regimes.

International groups will also want to remove any dormant or redundant entities that may otherwise be subject to stricter substance requirements.

The return of withholding taxes

A theme in the past few decades for the international tax system has been the rolling back of withholding taxes, reducing reliance on withholding as a way of allocating and collecting tax revenues internationally. This has been achieved through an expansion of bilateral tax treaties applying zero or reduced rates, EU directives to eliminate withholding taxes within EU groups, and domestic measures to repeal or restrict the use of withholding taxes.

More recently, that trend has started to go into reverse. This is partly because national tax authorities are emboldened to collect withholding taxes, and resist claims for relief, as a result of the developments discussed above on treaty shopping and the abuse of EU directives. But we are also seeing new types of withholding taxes being introduced.

It is interesting to note that the OECD pillar two proposal (for a global minimum tax rate) chooses to use a new category of withholding tax – immune from treaty relief – as a potential counteraction measure where a group’s local profits are otherwise taxed at below the 15% minimum rate. This is referred to in the OECD materials as the "subject to tax rule". We have also seen jurisdictions – including the UK – contemplating new and wider withholding taxes in relation to IP-related income.

Where are we now?

Our sense is that there are some developments that groups can respond to now, and others where a watching brief is needed as (potentially radical) changes are implemented at EU and international level.

In the first category, it is clear that national tax authorities are taking a tougher line on foreign holding companies and have higher expectations than in the past around substance, the absence of conduit features and the commercial rationale for holding structures. However, there is no one size fits all solution: each jurisdiction attaches weight to particular factors in a different way. For each investment, groups should assess what local expectations will need to be met to sustain successful claims for relief from withholding tax and non-resident capital gains tax.

In the second category, as well as monitoring developments in the BEPS 2.0 and ATAD 3 proposals, groups should be looking to monitor where they operate entities in low tax jurisdictions, entities with primarily passive income, and companies where the local substance may fall short on the types of criteria suggested by the EC (and discussed above). Once the key risks are identified, choices may include removing problematic holding companies, using different jurisdictions, or taking steps to bolster local substance. International groups with complex structures will benefit from taking steps early to get ahead of these changes.

This article was first published in the Tax Journal.

Get in touch