The decentralised future of corporate governance?

24 November 2022The Law Commission call for evidence shines the spotlight on decentralised autonomous organisations

The Law Commission has published a call for evidence on decentralised autonomous organisations (or “DAOs”). The Commission intends to understand how DAOs can be characterised and categorised and how the law of England and Wales might accommodate them.

The Commission’s project page sets out more on the project and its aims, whilst the call for evidence paper provides the detailed issues and questions on which the Commission is seeking feedback.

DAOs have long presented a potential challenge for legal systems, which may struggle to apply existing concepts of corporate law, financial and non-financial reporting, corporate governance and taxation to decentralised entities. The call for evidence raises some fascinating questions which the UK Government and courts will need to tackle sooner or later.

The Commission has asked for responses by 25 January 2023.

Below, we set out the background to the call for evidence and the key questions the Commission has raised, as well as some considerations that arise generally when structuring a DAO.

What is a decentralised autonomous organisation?

In the UK, there are various organisational models available to individuals or businesses wishing to pursue a particular venture, be it commercial, charitable or some other activity. These include:

- companies limited by shares, which are commonly used for commercial ventures;

- companies limited by guarantee, a popular choice for members’ and sporting clubs;

- limited liability partnerships (LLPs), used mostly by professional services businesses;

- ordinary or general partnerships, now less common but still popular for some businesses, such as general medical practices;

- limited partnerships, a popular investment fund vehicle;

- charitable incorporated organisations (CIOs), a form of charitable vehicle; and

- unincorporated associations, used for a variety of generally non-profit purposes.

Other potential choices include community interest companies (CICs), co-operative societies and community benefit societies.

A common feature of these organisational models is that they all require some form of active management. Members and investors will normally pool their assets within the venture, but responsibility and authority for making day-to-day decisions will typically be vested in some central body. In a company, this is the board of directors. Other models tend to allow for greater flexibility of management structure, although it is not uncommon to adopt a board formulation similar to a company.

Importantly, these models require human beings to interact and communicate to make decisions. Governance arrangements tend to revolve around holding meetings, debating key issues, voting on resolutions and updating books and registers. Decisions could range from commercial and operational matters, such as whether to enter into a major new contract, through to constitutional and organisational items, such as approving transfers of shares or other membership interests.

In the 21st century, much of this is now done electronically, using videotelephony and digital record-keeping, but the core process remains as it has been for centuries.

DAOs threaten to subvert this. In a DAO, the idea is that management is by its nature decentralised. Most DAOs achieve this by making use of distributed ledger technology (DLT). A particularly popular form of DLT is blockchain, the same framework that underpins cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin. DLT allows for the smooth dissemination of decision-making across the DAO’s participants.

This decentralisation of decision-making can be seen as a form of democratisation. Participants in the DAO enjoy more active involvement and have a greater voice in the management of the venture. That is not to say that existing organisational models cannot facilitate decentralised decision-making, but existing structures can make this fiddly.

In addition, aspects of the organisation’s activities and governance can be programmed to run automatically using smart contracts, which can execute themselves in certain pre-determined circumstances with little human intervention. (It is debatable whether smart contracts can self-execute without some level of human intervention, even if minimal, at some stage.)

The automation of certain aspects of governance is a further step towards adjusting the power balance in an organisation. By entrusting processes to self-executing programs, rather than exercising active oversight, the founders or management of an organisation relinquish control of the process to the general body of participants.

This can also bring commercial advantages for an organisation. Automating certain processes and devolving decision-making can potentially free up management time and introduce cost savings.

Part of the difficulty with identifying a DAO is that there is no consensus on the meaning of the term or its constituent elements: “decentralisation”, “autonomy” and “organisation”. The Law Commission has therefore asked for views on the definition of a DAO and its constituent elements.

What are the potential difficulties with DAOs?

DAOs are not new. There are already many thousands in existence across the world, often conducting decentralised finance (-“DeFI”-), investment and grant collection and allocation, artistic work and collectibles distribution, and crypto-token-related activities.

But, despite their growing popularity, the legal status of DAOs – how they own property, whether they can contract in their own name, whether they can incur liability – remains remarkably unclear.

A DAO is not a specific type of structure in its own right. DAOs can employ existing legal models (such as companies and partnerships) or exist purely as a network of functional processes. From a legal perspective, therefore, it is not possible to treat all DAOs in the same way. The legal framework that applies to a particular DAO will depend on precisely how the DAO has been constructed.

It is also clear that not many DAOs choose England and Wales as a forum. To understand why this might be, the Law Commission has asked for examples of DAOs that use the legal jurisdiction of England and Wales in their structuring arrangements.

The Commission intends to examine these questions and how, generally, DAOs can fit within the legal framework in England and Wales. Some of the Commission’s investigations and findings will influence the legal position in Scotland and Northern Ireland as well, but we have covered the call for evidence below solely from the perspective of England and Wales.

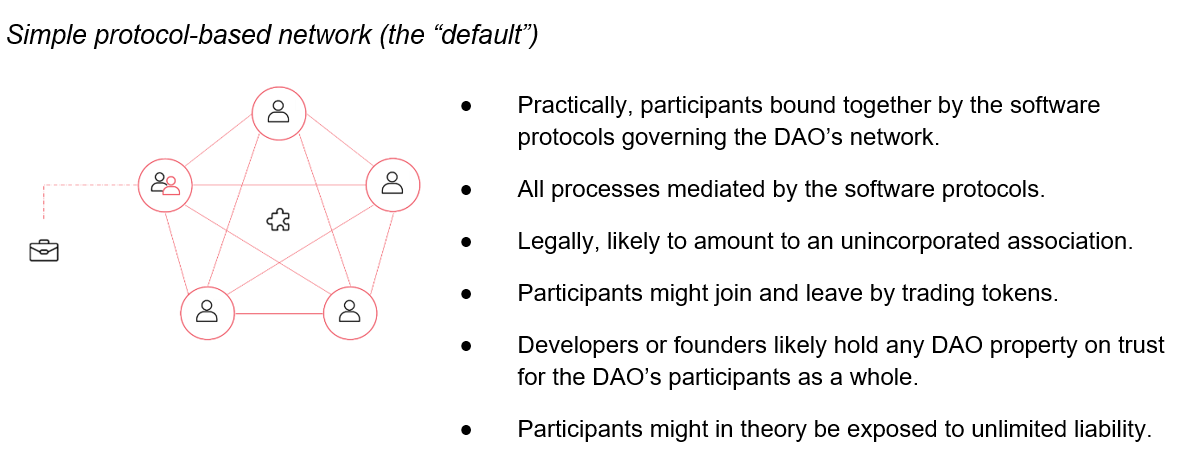

What legal form do DAOs take by default?

The Law Commission suggests that, as a “default” position, a DAO is likely to be categorised as an unincorporated association or a general partnership unless the founders and developers involved in creating the DAO take specific steps to adopt a different structure. The Commission has asked for views on this analysis and any experience in practice.

In England and Wales, unincorporated associations and partnerships have no legal personality of their own. The consequences of a DAO being classified as one of these structures are therefore significant.

- The DAO would not be able to own property in its own name. Instead, one or more individuals or legal entities would need to hold title to the DAO’s property as trustees for its participants. This will make acquiring and selling the DAO’s property, or using it as financial collateral, more difficult. The DAO will need to identify which persons will hold legal title, and those persons may (as trustees) become subject to fiduciary duties to the DAO’s participants. The Law Commission has asked for views on how trust law in England and Wales might apply to DAOs.

- The DAO would not be able to enter into contracts in its own name. Instead, one or more representatives of the DAO – in law, agents – would commit the DAO to contracts. It then becomes unclear precisely which participants in the DAO are liable on the contract. If the DAO is a general partnership, the position is clear: all partners will be potentially liable. If it is an unincorporated association, the situation is more complicated.

- The members may have unlimited liability to third parties. Structures such as unincorporated associations and general partnerships do not confer limited liability on their members. Subject to any contractual limits on liability that the DAO might negotiate, participants could stand to lose not merely what they have invested in the DAO, but potentially more.

- It may be harder to trade in the DAO’s “tokens”. Although the participants in an unincorporated association or partnership can come and go, they are normally unable to transfer their interest in the organisation to anyone else. By contrast, companies can issue shares that may be freely traded by investors. (Partnerships sometimes mimic this structure by issuing “units” – a process known as “unitisation” – although this tends to be limited to specific circumstances.)

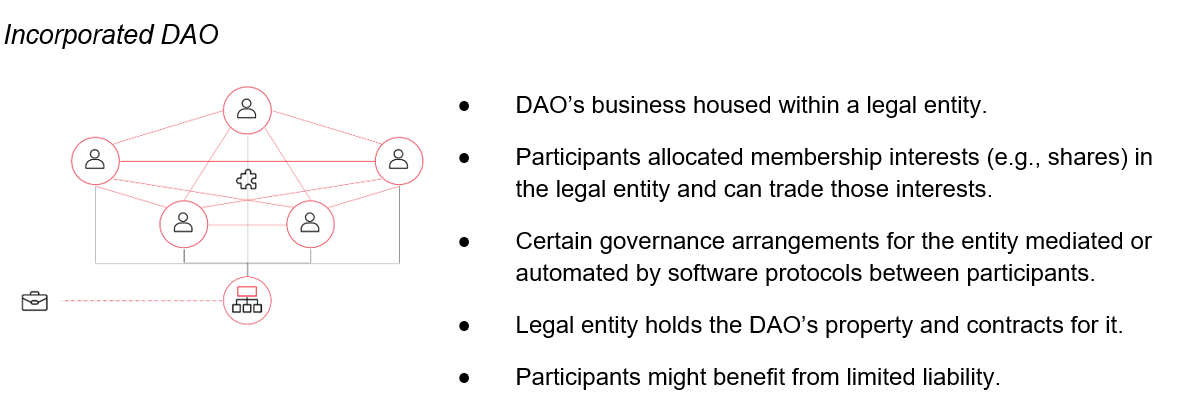

How can DAOs choose alternatively to structure themselves?

One way to address the difficulties described above is for a DAO to incorporate as a form of legal entity. For example, incorporating as a limited liability entity will afford participants in a DAO a degree of economic shielding against claims from third parties.

The call for evidence considers various types of legal entity that could be used for this purpose. A DAO could, of course, choose not to adopt a specific legal entity as its structure and instead rely on the “default” position.

The Law Commission has asked for views on problems and benefits that may ensue if a DAO chooses to incorporate as a legal entity.

A significant consequence (and, depending on the perspective of the DAO’s founders, drawback) of incorporating as a legal entity is that the DAO will inevitably undergo a degree of centralisation. This is a result of the more rigid statutory frameworks that govern incorporated entities and vest management responsibility and control in specific individuals.

Intuitively, this runs counter to the concept of a decentralised arrangement, with control and authority dispersed across the network of participants. However, the Commission notes that certain developers may actively wish to “recentralise” parts of their DAO, whether in exchange for the benefits of incorporation or to retain an element of control over certain facets of the DAO.

However, incorporation will also bring different challenges to a DAO.

- The DAO will need to appoint and disclose its officers and controllers. This includes details of its managers (e.g. its directors) and its members (e.g. its shareholders), as well as persons who ultimately exert control over it. Depending on how the DAO is structured, the pseudo-anonymous nature of participation could make ascertaining its participants and controllers very difficult.

- It may need to publicly file a copy of its constitution. For example, companies are required to make their constitutional documents public. This refers primarily to the company’s articles of association and certain resolutions of its members, although any document with constitutional significance (e.g. in some circumstances, a shareholders’ agreement) may need to be filed. Working out precisely what to file – and how – may be particularly tricky where parts of the DAO’s constitution incorporate or are embodied in software protocols and/or smart contracts.

LLPs are not required to file a copy of their constitution and, whilst companies limited by guarantee do need to file their articles, they can keep a separate set of “by-laws” that govern certain operational matters. These types of organisation may provide more flexibility for a DAO in this respect. At the other end of the spectrum, any charitable organisation must generally obtain Charity Commission approval before it can alter its constitution, which may be awkward for an entity that wishes inherently to devolve control over its structure.

- It will need to keep a register of its members. This might include only a subset of the DAO’s participants, such as the founders and developers, or a broader constituency, such as the DAO’s token-holders (if it chooses to issue crypto-tokens) or, indeed, all the network participants. Statute requires a register of members to contain specific information, which will need to be replicated somehow within the DAO’s network. Again, DAOs may find it difficult to track and identify members from time to time.

- It may need to start producing accounts. All companies (other than unlimited companies) and LLPs, for example, are required to prepare accounts for their members (although the content and publication requirements will differ, depending on the size and nature of the entity’s business). Larger DAOs may even find themselves subject to requirements to have their accounts audited.

- Difficulties may arise if the DAO grows large. Further reporting requirements may arise, including the need to produce climate disclosures and (if the DAO becomes very large) a corporate governance statement. The DAO may also reach a natural critical mass before it requires external financing. Its structure will determine whether and (if so) how it can attract external investment, whether through private debt, private equity or the capital markets.

- The DAO’s founders or developers may incur legal duties. For example, if the DAO incorporates as a company, any founders that become directors will owe statutory duties to the DAO itself, including to promote its success for the benefit of its members (whoever they may be). That is not to say founders and developers won’t incur legal duties to the DAO’s participants if they choose not to incorporate as a legal entity, but the nature of those duties may differ.

- The DAO may become subject to capital maintenance requirements. This will be relevant if the DAO is being set up as an investment vehicle or for-profit business. UK companies, for example, cannot distribute their capital back to members unless they undergo specific (often cumbersome) procedures, and they can share any gains among their members only if they have sufficient “distributable profits” to do so. Charitable and quasi-charitable entities may well have an “asset lock” that outright prohibits them from making distributions to their participants. Other entities, such as LLPs, have no such restrictions.

Outside England and Wales

The Law Commission notes that most DAOs appear to establish themselves outside England and Wales. It asks why this is and suggests that one reason might be the availability in other jurisdictions of legal models that are more suitable for DAOs.

The paper gives the Swiss “foundation” (Stiftung-/-fondation-/-fondazione) – a legal entity with no shareholders or other economic participants – as an example (although similar structures exist in other jurisdictions). We typically see foundations used for charitable purposes, in estate planning or as an alternative to trust structures, but there is no reason they cannot be adapted to act as a DAO.

The Commission suggests that a DAO might use a foundation as a repository for tokens, intellectual property or other assets, or to enter into contracts for the DAO, with the foundation’s directors being obliged to act in the best interests of the DAO. The paper acknowledges that DAO founders might also choose foundations due to favourable tax treatment or regulation in the foundation’s jurisdiction.

Other models the paper contemplates include special purpose trusts (trusts that operate towards a particular objective, rather than for the benefit of particular persons) and specific blockchain and DAO legal entities in some jurisdictions. These models do not exist in England and Wales.

In light of this, the Law Commission asks whether there is a case for creating a new type of legal entity in England and Wales that is specifically tailored for DAOs. The Commission notes that this would inevitably involve an element of (re)centralisation for a DAO and that any new entity type would need to be subject to some element of registration, reporting and transparency requirements.

The concept of “partial decentralisation”

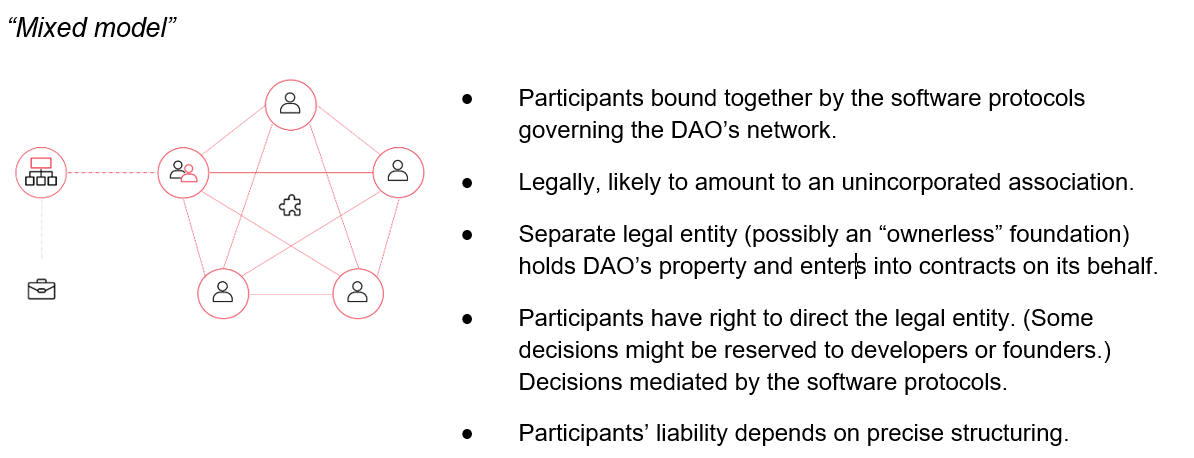

Finally, the Commission explores the concept of decentralising and relinquishing control over selected elements of a DAO’s architecture and activities without using a legal entity. This might include using open-source software and self-executing code to devolve or automate certain processes.

One such approach is for the DAO to employ one or more legal entities or trusts, but not to house the DAO exclusively in a legal entity. In this way, the framework of the DAO can exist as an unincorporated arrangement (perhaps a contractual matrix) between the network participants, but with an incorporated entity holding the DAO’s property, taking significant operation or commercial decisions and entering into contracts on its behalf.

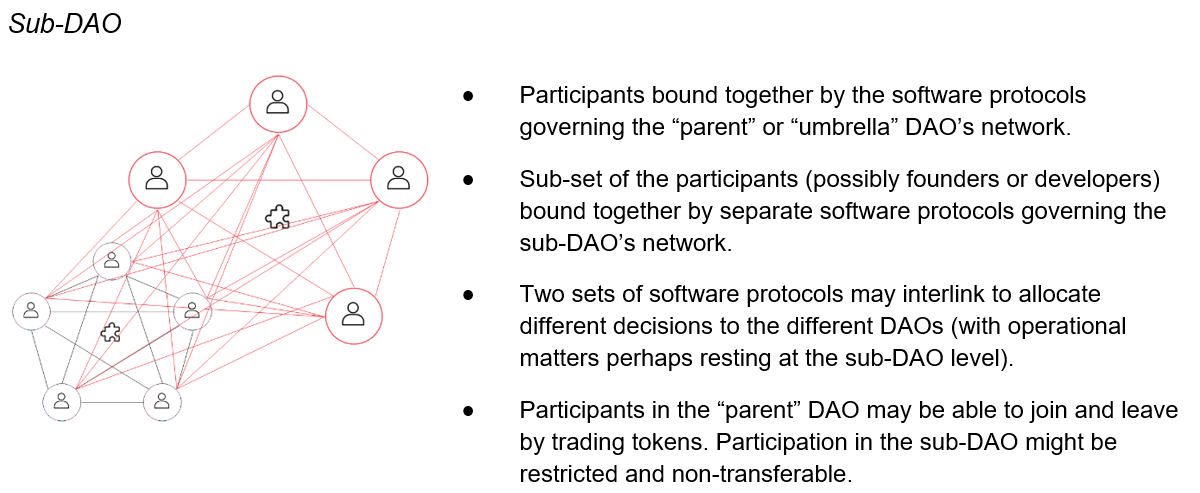

Indeed, some DAOs may choose to establish “sub-DAOs” to carry out certain operational aspects of the wider DAO. A sub-DAO may well have a different network of participants from its parent or umbrella DAO, with each DAO enjoying differing levels of control and authority.

In all likelihood, these kinds of “mixed model” may well provide the most suitable framework for larger and more ambitious DAOs that wish to pursue a defined business strategy, rather than act simply as an investment pool or trading platform. A fully decentralised framework may make it difficult for the DAO to take rapid and informed strategic decisions, whereas a fully incorporated arrangement may well nullify the anticipated benefits of decentralisation. A “mixed model” may provide a happy medium.

The Commission concludes that the law of England and Wales is sufficiently well-developed and flexible to accommodate mixed models of this kind. However, given that DAOs seldom choose England and Wales to establish themselves, the Commission is keen to understand what obstacles exist.

Some different possible models for a DAO

There is no limit to the number of ways in which a DAO might be arranged. We have set out some simplistic structures below. In practice, a DAO may well incorporate a blend of these.

The issue of “tokens”

DAOs often issue some form of crypto-token to persons who participate in their network (although there is no need for a DAO to do so in order to operate). The token will normally be issued according to software protocols that govern the operation and framework of the DAO itself.

Crypto-tokens can, like currency, serve as a simple means of exchange (e.g. Bitcoin and Ethereum), or, like derivatives, they can represent an interest in real-world assets (e.g. commodities, debts or other contractual rights, real estate or securities). Indeed, crypto-tokens can be linked to other crypto-tokens on the same or another network.

Alternatively (or in addition), crypto-tokens can embody the rights of participants in the DAO’s network. This may include the ability to vote on particular decisions. Tokens that carry both rights and an economic entitlement to underlying assets are not at all dissimilar to shares in a company and, indeed, in some jurisdictions, may be regulated as securities.

Crypto-tokens can be freely tradeable (e.g. on a market or exchange) or exclusive to the persons to whom they are allocated (as is often the case with non-fungible tokens (or NFTs)).

A DAO might issue tokens to all its network participants or only to a smaller number of participants, such as its founders and developers. A DAO can issue different kinds of token to different constituencies, with each type of token carrying different economic and participatory entitlements, in much the same way as companies can issue different classes of share.

The Law Commission is asking for views on the extent to which DAOs use crypto-tokens to confer rights and economic interests on their participants in much the same way as company shares and partnership interests. It also seeks views on the extent to which token-holders should be liable to users of a DAO’s network.

The Commission is also asking for views on how the degree of control the developers of a DAO exercise over tokens issued by the DAO may, in turn, inform those individuals’ potential liability. The greater the control they wield, arguably the more likely it is a court will find that the developers have undertaken a duty of care or fiduciary duties towards the DAO’s token-holders.

This will depend heavily on the facts in each case, including how the DAO’s network is structured, the economic and participatory rights of token-holders, how static the DAO’s participant base is, and how far matters have been decentralised across the network. However, it is an important factor for founders and developers to consider when structuring a DAO.

Other matters on which the Commission is seeking views

Towards the end of its call for evidence, the Law Commission asks for views on a variety of related topics. These include:

- the extent to which DAOs make use of smart contracts and whether smart contracts themselves should have legal personality;

- how the privacy of participants in DAOs can be protected;

- the interaction of incorporated entities and open-source software protocols;

- how the law should govern the relationship between different constituent elements of a DAO; and

- the extent to which DAOs may be subject to anti-money laundering obligations.

The Commission has also asked for views on how DAOs structure their arrangements in relation to a variety of matters, including protocol development, intellectual property, governance decisions, finance, personnel, administration, and disputes between participants.

Finally, the Commission has asked for views on how the market understands the tax position for a DAO and on any areas of uncertainty. The paper acknowledges that this will depend heavily on the way in which a DAO is structured (particularly where it makes use of one or more legal entities).

Next steps

At this stage, the Law Commission is embarking merely on a “scoping project”. It has not been asked to deliver any recommendations for reform. However, should it be tasked with this, feedback delivered through the call for evidence will prove invaluable.

DAOs represent an emerging and exciting development in the corporate world. Although still regarded with suspicion by many, there is no doubt that DAOs are becoming more popular and widespread.

Clearly, DAOs are not suitable for all types of venture, but ability to introduce automation, dispersed decision-making and straightforward participation for the general public make them attractive and interesting propositions which will no doubt receive increasing focus over time.

Get in touch