Unpacking Pillar Two: transfer pricing

21 April 2022Because the GloBE rules look at an MNE group’s effective tax rate (ETR) on a country-by-country basis, the question of how a group’s profits are allocated between countries is of fundamental importance. In common with most countries’ domestic tax systems, the GloBE rules require cross-border intra-group transactions to be priced in accordance with the arm’s length principle (ALP).

The Model Rules state the transfer pricing requirement succinctly, however there are several nuances in the commentary that are not apparent from the basic rule and which warrant detailed consideration.

How does the GloBE transfer pricing rule work?

The core GloBE transfer pricing rule is straightforward: transactions between Constituent Entities located in different jurisdictions must be priced in accordance with the ALP if that differs from the price recorded in the entities’ accounts. The GloBE rules rely on normal OECD transfer pricing principles for determining what that arm’s length price is.

Importantly, the GloBE rules apply on the basis that the local tax authorities of the Constituent Entities are best placed to judge whether the pricing of a transaction complies with the ALP. There is therefore a presumption that if those local tax authorities agree a transfer pricing adjustment, or agree that no adjustment is required, or decline to challenge the returned position, then the transaction is appropriately priced and no further adjustment is required for GloBE purposes. Taxpayers can therefore rely on bilateral APAs or the conclusions of local tax audits, and this cannot be called into question by a third tax authority that is applying the Income Inclusion Rule or Undertaxed Profits Rule. This is a pragmatic approach that should limit the scope for the GloBE rules to create new transfer pricing controversy for groups.

How are unilateral adjustments dealt with?

The approach described above provides a definitive position when a cross-border transaction is returned at the same transfer price in both countries, however this will not always be the case. Different pricing can occur when one country makes a unilateral adjustment to a transaction price, say on conclusion of an audit, but the group is then unable to obtain a corresponding adjustment in the other country.

The GloBE rules recognise that this is the practical reality for many MNE groups. They deal with it by respecting unilateral transfer pricing adjustments for GloBE purposes, except where that would lead to income being taken into account under the GloBE rules twice or not at all.

That policy is given effect in a rule that says unilateral transfer pricing adjustments should be reflected, together with a corresponding adjustment, in a group’s GloBE profits except where the unilateral adjustment is to the profits of an under-taxed jurisdiction. An under-taxed jurisdiction is defined as one with a nominal rate below 15%, or where the GloBE ETR was below 15% in each of the two years preceding the unilateral adjustment. Essentially this is a means of identifying jurisdictions that are very likely to be subject to a GloBE top-up in the current year.

The logic behind this rule is subtle: while a unilateral adjustment made in an under-taxed jurisdiction would be effective for GloBE purposes (it adjusts the profits in a jurisdiction that is subject to a GloBE top-up), if the corresponding adjustment is made in a highly taxed jurisdiction it will not be effective either for GloBE purposes (because the jurisdiction is highly taxed and no top-up charge arises) or for domestic purposes (because no corresponding adjustment was made for domestic tax purposes).

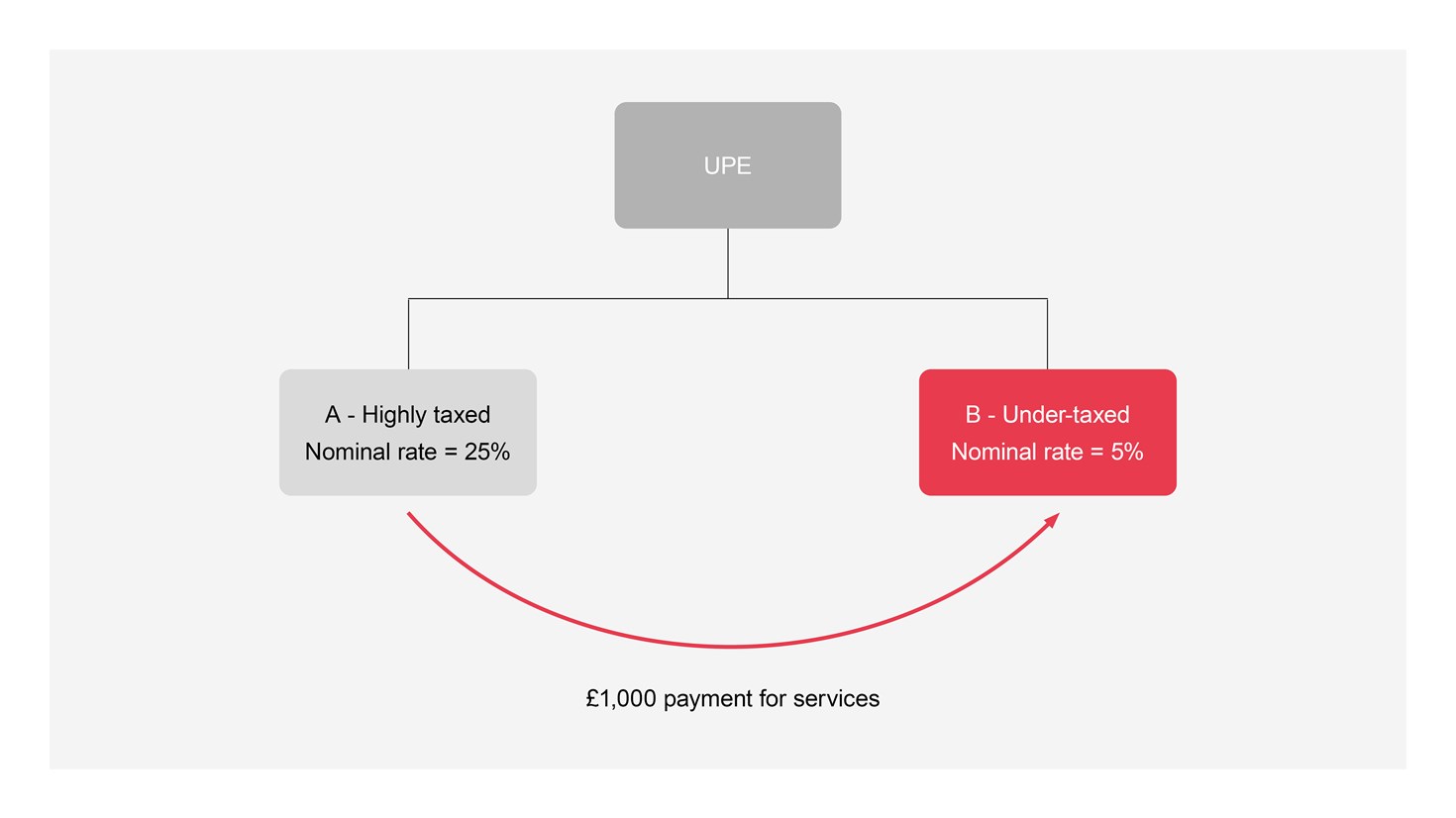

This is perhaps best demonstrated by reference to an example. Consider the following situation, in which a highly taxed Constituent Entity pays a service fee to an under-taxed Constituent Entity:

Entity A records an expense of £1,000 in its accounts and Entity B records corresponding income of £1,000, both based on the contractual price

Scenario 1

Suppose Country A’s tax authority makes a unilateral transfer pricing adjustment that reduces the expense recognised by Entity A for tax purposes by £300, to £700.

In that case, if the GloBE rules looked only to the entities’ accounting profits without making a transfer pricing adjustment £300 of income would be taxed twice:

- firstly, under the domestic tax system of Country A, which only permits a deduction of £700; and

- secondly, by way of a GloBE top-up paid in respect of Entity B, which recognises the full £1,000 payment.

To prevent this the rules therefore adopt the unilateral adjustment made by Country A (thereby reducing Entity A’s accounting expense and increasing its profit) and make a corresponding adjustment to the GloBE income of Entity B, reducing it to £700. This ensures symmetrical treatment and no double taxation.

Scenario 2

Suppose instead that Country B’s tax authority makes a unilateral transfer pricing adjustment that increases the income recognised by Entity B for tax purposes by £200, to £1,200.

This time adopting the unilateral adjustment, and a corresponding adjustment to Entity A’s expense, for GloBE purposes would lead to £200 of income being taxed twice:

- firstly, under the domestic tax system of Country A, which only permits a deduction for the £1,000 payment (an outcome which is not affected by the GloBE corresponding adjustment); and

- secondly, by way of a GloBE top-up paid in respect of Entity B, which would have adjusted GloBE income of £1,200.

The unilateral adjustment made by Country B is therefore ignored for GloBE purposes – Entity B’s accounting income is not increased, and nor is Entity A’s accounting expense. To the extent Entity B pays domestic tax on an increased measure of profit, that additional tax increases its GloBE ETR.

Same-country transfer pricing

There is no general requirement in the GloBE rules to adjust transactions between constituent entities in the same country to an arm’s length price. Given that the rules aggregated entities’ results on a country-by-country basis the pricing of such transactions should not impact on the amount of GloBE income determined for each country.

There are two exceptions:

Firstly, the ALP must be applied to any same-country asset transfers that result in a loss. The Commentary explains that this is intended to prevent groups from manufacturing non-arm’s length losses by transferring assets within the group at an undervalue. It seems that, by implication, groups are permitted to crystallise losses by transferring assets within the group provided those losses reflect the arm’s length position.

Secondly, the ALP must be applied to same-country transactions where one of the parties is either an excluded entity or an entity – such as an investment entity or a minority-owned constituent entity – that has its GloBE ETR calculated separately from the rest of the group. This simply recognises that in such instances the transacting entities’ results will not be aggregated so their GloBE profits will be sensitive to the transfer price.

Administration

Transfer pricing is inherently judgmental and it is not unusual for groups’ returns to be adjusted several years after filing where one or more tax authorities disagrees with the returned position. Neither the Model Rules nor the commentary say how such disputes, and the resulting post-filing adjustments to profits, should be dealt with. The commentary indicates, however, that this will be considered as part of the further work on the GloBE Implementation Framework. The rules that the OECD develop will need to ensure that profit adjustments are made in the same period as adjustments to Covered Taxes – under Article 4.6 increases in tax are adjusted in the current period, rather than the historic period to which they relate.

Keep up to date with the latest developments and other useful information on our OECD BEPS 2.0 hubpage.

Get in touch