Contract transfers: substance over form

01 March 2023Contract was novated by conduct, despite lack of prior written consent

The Court of Appeal has held that a contract between five parties was effectively novated, then novated again, even though the documentation did not refer to all the parties and prior consent had not been given.

- A novation is useful where a party to a contract wishes to transfer all its rights and obligations under the contract to someone else, but it will require the contract counterparty’s consent.

- Novations are normally set out in a written consent, but they can take place informally, including by conduct if the parties act in a way that indicates a novation has occurred.

- This may happen, even if the contract contains specific formalities for transferring rights and obligations, such as a requirement for prior written consent.

What happened?

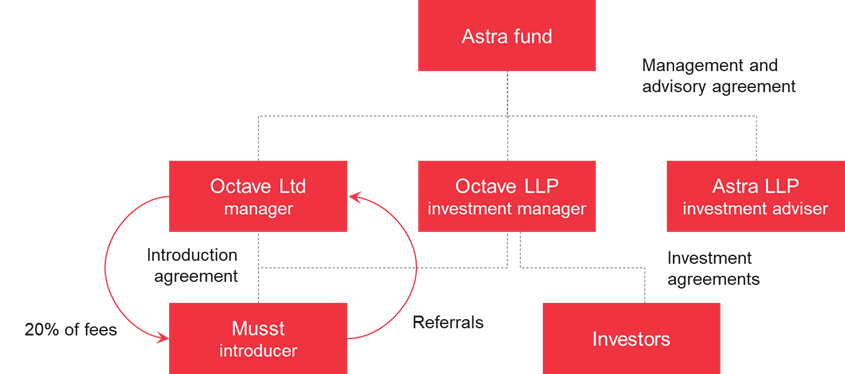

Musst Holdings Ltd v Astra Asset Management UK Ltd [2023] EWCA Civ 128 concerned a contract for the introduction of clients to an asset management business.

The contract arose out of discussions between a Mr Siddiqi and a Ms Galligan (who were spouses) and a Mr Mathur. The individuals agreed to set up an arrangement under which Mr Siddiqi and Ms Galligan would introduce contacts to Mr Mathur so that those contacts could invest in asset-backed securities through Mr Mathur’s asset management business.

Mr Siddiqi and Ms Galligan would effect the introductions through Musst Holdings Limited (Musst), an entity owned by Mr Siddiqi.

Mr Mathur intended to run the asset management business through a new organisational structure called “Astra". To this end, he established Astra Asset Management UK Limited (Astra Ltd) and Astra Management LLP (Astra LLP).

However, at that time, neither Astra Ltd nor Astra LLP had the necessary regulatory approvals to carry out the asset management business. So, instead, Mr Mathur decided to initiate the business through another organisation – “Octave” – which did have the appropriate regulatory approvals.

To this end, Mr Mathur established a fund, which contracted Octave Investment Management Limited (Octave Ltd) to act as its “manager” and Octave Investment Management LLP (Octave LLP) to act as its “investment manager”. The fund also contracted Astra LLP to act as an “investment adviser”.

Subsequently, Musst, Octave Ltd and Octave LLP concluded an “introduction agreement” to embody the agreed arrangement. Under the agreement, Octave Ltd agreed to pay Musst a 20% share of management and performance fees received from clients whom Musst introduced to Octave and who invested in asset-backed securities. Astra LLP was not a party to the introduction agreement.

Octave Ltd assumed the responsibility for paying fees under the introduction agreement. Octave LLP’s role was purely administrative.

The introduction agreement resulted in two contracts with two investors in the fund.

The diagram below illustrates the initial contractual arrangements:

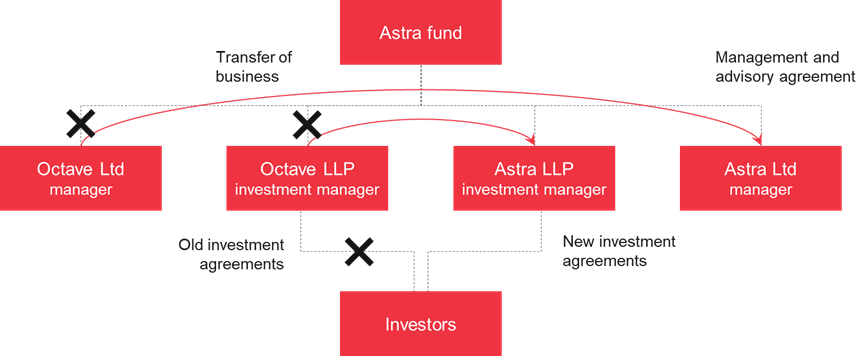

All parties understood at the time that Mr Mathur intended to “spin out” these operations into the new Astra entities once they had received the necessary regulatory approvals. The FCA granted those approvals just over a year later, at which point Astra Ltd and Astra LLP replaced Octave Ltd and Octave LLP as the fund’s manager and investment manager respectively.

A month later, Octave LLP and Astra LLP agreed in correspondence that Astra LLP would take over Octave LLP’s investment management responsibilities, that fees payable to Octave Ltd would instead be payable to Astra Ltd, and that Octave Ltd’s obligations would transfer to Astra Ltd.

Following this, Octave and Astra entered into replacement agreements with the two investors, effectively moving them across from Octave to Astra. In both cases, an individual who worked for Octave (and who later transferred to Astra) informed Musst of the transfer and asked Musst to invoice Astra LLP going forward.

The diagram below illustrates the changes:

Following this, a representative of Astra (who had moved over from Octave when the transfers happened) sent a revised version of the introduction agreement to Musst, in which Octave Ltd’s and Octave LLP’s names were replaced with Astra Ltd and Astra LLP. The representative explained that this was “effectively a name-changing exercise”. However, the revised version was never signed.

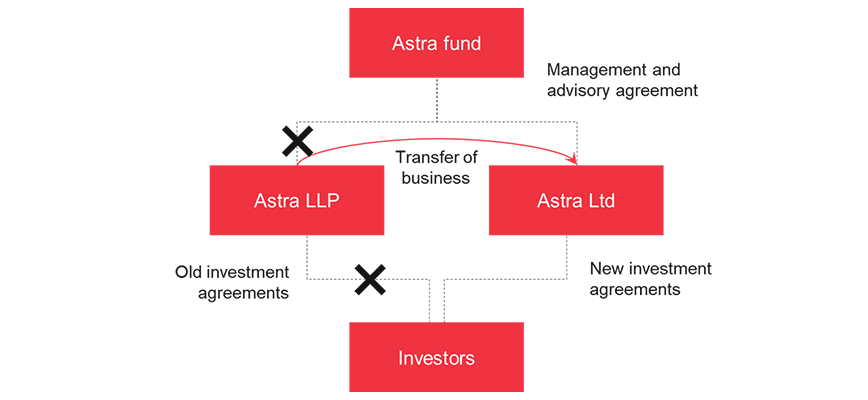

Just under a year later, Astra LLP formally transferred its business to Astra UK, and Astra UK entered into revised agreements with the investors. The diagram below illustrates this final step:

What was the dispute?

A dispute later arose about payment of the referral fees to Musst under the introduction agreement.

According to the judgment, the dispute arose after Astra Ltd began experiencing cashflow difficulties and failing to provide the financial information Musst needed to render invoices under the introduction agreement. Ultimately, Astra Ltd ceased paying the fees to Musst and denied liability.

Musst brought a claim against Astra Ltd for breach of the introduction agreement. It claimed that the introduction agreement had been novated: (i) first, from Octave Ltd and Octave LLP to Astra Ltd and Astra LLP; then (ii) subsequently, from Astra LLP to Astra Ltd.

Musst claimed that the novation had taken place by conduct, that is to say, without any formal legal documentation but by virtue of the way the parties had all acted.

Suppose that two parties (X and Y) enter into a contract.

Circumstances may arise in which X may wish to transfer that contract to someone else (Z). This might happen, for example, because X is selling their business and assets to another person, or because X’s group of companies is undertaking group restructuring.

One way to transfer contractual rights is by making an assignment. Under this process, X and Z enter into an assignment agreement, then one of them serves a written notice on Y notifying them that X has assigned the contract to Z.

A theoretical advantage of assignment is that it does not require the consent of the original counterparty (in this case, Y), although sophisticated commercial contracts normally contain provisions prohibiting an assignment without the counterparty’s written consent.

One drawback of an assignment is that, under English law, a person can assign their rights under a contract, but not their obligations. So, X would remain liable under the contract even after they have assigned it to Z and stopped performing it. The rationale for this is that X’s identity and financial standing may be important to Y and so Y is entitled to assume they will be dealing with X throughout the lifetime of the contract.

The other way to transfer a contract is novation. Under this process, X, Y and Z collectively agree that, from a specific point in time, the contract will continue with Z performing X’s obligations and enjoying X’s rights under the contract.

The key advantage of a novation is that a person can transfer both their rights and their obligations under a contract. This allows X to draw a “line in the sand” and gain a “clean break” from the contract.

However, unlike an assignment, a novation will always require the counterparty’s consent. For this reason, novation is usually restricted to contracts that are more material to a business (whether due to their value or their strategic significance).

Technically, a novation involves terminating the old contract between X and Y and creating a brand-new contract between Z and Y. Normally, this is done through a novation agreement that sets out exactly what liabilities Z is assuming, including (in particular) whether Z is taking on X’s obligations only going forward or whether Z will also be taking on X’s historic liabilities under the contract. The novation agreement may also provide a mechanism for X and Z to cross-indemnify each other.

However, the courts have also found that it is possible for a novation to take place by conduct if a novation is a necessary explanation for the parties’ subsequent conduct.

Astra argued that there could not have been any novation. It pointed to clause 17 of the introduction agreement, which stated:

“This agreement is personal to the parties and neither party shall assign, transfer, mortgage, charge, subcontract, or deal in any other manner with any of its rights or obligations under this Agreement without the prior written consent of the other party.”

Astra argued that clause 17 prevented both a novation from the Octave entities to the Astra entities and a subsequent novation from Astra Ltd to Astra LLP unless Musst had given its written consent in advance. In particular, the requirement for written consent meant that a novation could not take purely by conduct without being documented.

That had not happened, and Musst had not given its consent in advance, and so, Astra argued, the novations had not occurred.

What did the court say?

Upholding the High Court’s original decision, the Court of Appeal found that both novations had occurred.

As soon as Octave had stepped out of the picture and Musst had started addressing its invoices to Astra, a relationship had commenced between Musst and Astra along the terms of the introduction agreement.

In reality, Octave and Astra were closely related, working from the same address with an overlap of staff. From a commercial perspective, this was merely a change in name.

All the parties had known from the outset that Mr Mathur intended to spin the business out from Octave into Astra after Astra received regulatory approval. The change from Octave to Astra would not, therefore, have come as a surprise.

The court was not swayed by the fact that, although it was Octave Ltd that had undertaken the principal duties under the introduction agreement, only Octave LLP and Astra LLP had corresponded in relation to the novation. Astra LLP had agreed to take on the obligations of both Octave Ltd and Octave LLP. Indeed, in the court’s words, “the protagonists at both Octave and Astra paid scant regard to the existence of separate entities when dealing with each other”.

What about the “prior written consent”?

The court said it did not matter that Musst had not provided written consent to the transfer in advance. It had been open to Musst to waive the requirement for prior written consent and instead to provide consent after the event, which is what had happened. Musst had therefore given its consent.

The judgment does, however, highlight a slightly difficult conceptual issue. Astra had, in effect, argued that Musst could not have waived the requirement for consent in advance, because clause 17 required any consent to be in writing. A waiver would also, therefore, need to be in writing.

There is some logic to this argument. If Musst had been able to waive, orally or by conduct, the requirement for written consent, then there would arguably be no point in requiring written consent. In effect, a waiver would amount to a consent and could be given in non-written form.

In support of this argument, Astra referred the court to the recent case of MWB Exchange Centres Ltd v Rock Advertising Ltd [2018] UKSC 24. In that case, the Supreme Court upheld the efficacy of contractual “no oral modification clauses”, which state that variations to a contract cannot be made unless set out in writing. (For more information on that case, see our previous Corporate Law Update.)

In this case, however, the court said that the restriction on transfers without consent was a different kind of clause, and that there was already case law allowing a contract party to give consent retrospectively after a novation had taken place.

This is true, but it does create an awkward tension between the concept (on the one hand) that consent to novation can be given informally and after the event and (on the other hand) that requirements for particular variations to be in writing cannot be bypassed orally or by conduct.

That tension is compounded in this case, because clause 16 of the introduction agreement contained a “no oral modification clause”, stating that no variation of the introduction agreement would be effective unless made in writing. The court justified its decision on the basis that a novation is not a “variation”; rather, it is the extinction of one contract and the creation of a new one.

But the question arises whether waiving a requirement for written consent to a novation is a variation. Certainly, an oral waiver or waiver by conduct was a departure from the terms of the introduction agreement, but was it a “variation”? The distinction will no doubt often be difficult to perceive.

Ultimately, the factual matrix and the court’s decision are not dissimilar to those of a similar case (Gama Aviation (UK) Ltd v MWWMMWM Ltd [2022] EWHC 1911 (Comm)), on which we reported last Summer. See our previous Corporate Law Update for more details on that case.

What does this mean for me?

In the end, it does seem that common sense prevailed.

Whatever the reasoning, there is no doubt that all parties had been aware of the intention that the business and contracts would ultimately rest with Astra, not Octave. Octave, Astra and Musst all behaved on the basis of that intention, and Astra’s arguments to the contrary seem to have arisen only after it started encountering financial difficulty.

However, the case is an important reminder of the value in documenting transfers of contracts properly. In the case of a novation, this includes identifying all parties to the contract that is to be transferred and ensuring they sign the novation agreement. This will enable the parties to understand their responsibilities to each other moving forwards and avoid unnecessary disputes.

When looking to novate a contract, the following are useful tips to bear in mind.

- Describe the contract properly. Often, there will be several contracts between any two given organisations. Identifying precisely which contracts are to be novated will be key, particularly where an organisation is selling part of its business (such as a division) but retaining other parts.

- Identify all the parties to the contract. It is not uncommon for contracts to have multiple parties but with only two or three of those parties in practice carrying out day-to-day activities. Nevertheless, all the contract parties should sign the novation to avoid disputes.

- Establish who will be taking on what responsibilities. On a simple novation, the outgoing party will simply be transferring all its obligations to the incoming party. However, in more complex arrangements, a single incoming party may be taking on the responsibilities of more than one outgoing party, or a single outgoing party’s obligations may need to be split between different incoming entities. In some cases, the contract may handle various service lines, with only some being novated and some being retained by the outgoing party. The novation agreement should spell all of this out in detail.

- Deal with legacy liabilities. It is a given that the incoming party will be taking on the outgoing party’s future obligations. But what about historic liabilities and obligations? Will the incoming party be responsible for these, or will the outgoing party remain liable for any performance failures, fees and so forth up to the point of novation? Again, the agreement should deal with this.

- Check any transfer restrictions in the contract. Often, a contract will state that any transfer of rights or obligations requires the counterparty’s consent. This is required anyway for a novation, but there may be formalities to follow. The judgment in this case suggests that the parties may be able to novate without following all formalities, but it will usually be better to avoid any doubt.