Brussels vs Big Tech: DMA battle lines drawn

23 May 2024The Digital Markets Act (DMA) is a landmark regulation that aims to curb the power of large online platforms in the EU and foster fair competition in digital markets.

It specifically targets large online platforms – in particular, designated “gatekeepers” operating “core platform services” (CPS) which serve as important gateways for business users to reach end users.

Overview of recent developments

Further to our previous updates on the DMA1, click here for a timeline of key developments since the regulation was implemented.

New horizons: what is happening now?

With the initial notification and designation processes largely concluded, and nearly all the designated gatekeepers’ compliance measures revealed, the Commission has moved past the opening, more procedural phases of the DMA’s implementation. Going forward, it is the more contentious and adversarial aspects of the regime that are likely to take centre stage, with the battle lines already being drawn across a number of fronts.

Non-compliance investigations

As noted above, on 25 March the Commission opened non-compliance investigations under Article 20 of the DMA against Alphabet, Apple and Meta. In particular, it is scrutinising:

- Alphabet’s and Apple’s rules regarding app developers’ ability to promote offers to and conclude contracts with app-users through channels other than Google Play and App Store respectively. The Commission is concerned that those rules – in the form of fees and restrictions on developers – may breach Article 5(4) of the DMA, which prohibits so-called "anti-steering" provisions and seeks to allow developers to direct consumers to alternative offers without undue restrictions;

- Apple’s iOS web browser choice screen, and iOS users’ ability to delete certain apps from their iPhones. Article 6(3) of the DMA requires gatekeepers to allow users to easily change their default settings and web browser and to delete any pre-installed apps. The Commission is concerned that the design of Apple’s web browser choice screen deprives end-users of the ability to make a fully informed decision, as they cannot adequately explore the other options available to them. The Commission has also noted that some iOS apps (such as Photos) cannot be deleted entirely;

- Meta’s new “pay or consent” model, under which users have to pay a monthly subscription fee to use Facebook and/or Instagram without targeted advertising. The Commission is concerned that this model fails to comply with Article 5(2), which requires gatekeepers to obtain user consent for the combining or cross-use of personal data, on the basis that any such consent will not have been freely given; and

- Alphabet’s potential preferencing of its own vertical search services (such as Google Shopping and Google Hotels) when displaying Google Search results. The Commission is concerned that these services still benefit from favourable treatment, in breach of Article 6(5) of the DMA, which prohibits self-preferencing of gatekeeper services in rankings and indexing.

The Commission’s investigations are expected to conclude within a year. The Commission has the power to compel the production of information, carry out (voluntary) interviews and conduct physical inspections. If non-compliance is confirmed, the investigations could result in substantial fines, of up to 10% of global turnover, as well as orders to cease and desist with the non-compliance.

Additional enquiries and measures

As well as the above concerns – in respect of which the Commission says it already has “concrete evidence of possible non-compliance” – the Commission is investigating: (i) whether Amazon is treating all products on its Amazon Store fairly and not favouring its own-brand products; and (ii) Apple’s new App Store business model, including the fee structure for developers who choose to distribute apps other than via the App Store.

Under the DMA, the Commission is able to exercise its investigative powers before formally opening proceedings under Article 20. If the Commission’s preliminary concerns are substantiated, these enquires will lead to further non-compliance investigations being opened.

Further, and as also noted above, the Commission has issued retention orders to several gatekeepers requiring them to preserve documents relevant to assessing their compliance with the DMA.

Ongoing appeals and challenges

Beyond the above-mentioned investigative proceedings, five appeals are pending before the EU General Court in respect of decisions taken by the Commission under the DMA.

- Most notably, ByteDance has challenged its designation as a gatekeeper in respect of its social media platform TikTok. ByteDance also applied for interim relief suspending the application of the DMA conduct obligations pending the determination of its appeal, on the basis that, upon entry into force, those obligations would irreparably harm its business. However, on 9 February 2024 the General Court dismissed that application, instead granting ByteDance an expedited trial. This marked the first time a General Court ruling has addressed the DMA.

- Meta disputes the designation of Facebook Messenger and Marketplace as CPS – claiming that they are integral components of the Facebook social network CPS (which it accepts must follow the requirements of the DMA) and should not be treated as, respectively, a distinct number-independent interpersonal communication service (NIICS) and a distinct online intermediation service.

- Apple has challenged: the designation of iOS as an important gateway insofar as it imposes interoperability obligations on it; the designation of App Store as a single CPS; and the treatment of iMessage as a NIICS. In a separate appeal, Apple also challenged the decision to open a market investigation into iMessage, though this is now a moot point given that the Commission went on not to designate iMessage as an important gateway.

All these appeals raise significant questions of interpretation under the DMA. In determining them, the General Court will need to assess whether the Commission has committed material factual errors in its approach to designating CPS, followed all essential procedural requirements, and/or acted in accordance with the principle of proportionality.

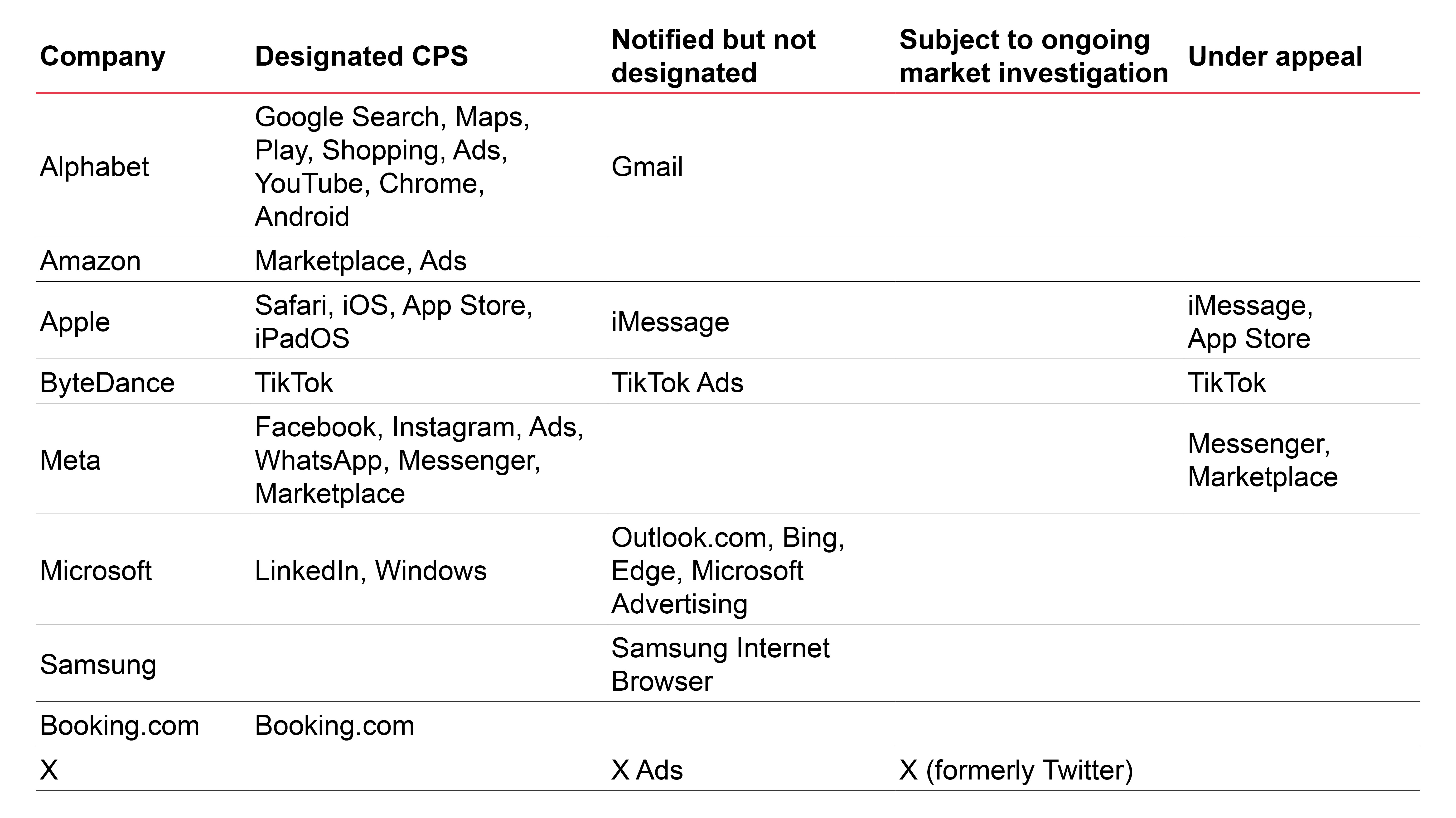

Who has been designated for what?

The table below summarises the outcome of the gatekeeper CPS notification and designation process.

What have we learned so far?

Over the last nine months, the Commission has acted boldly in its implementation and enforcement of the DMA. It has shown a willingness to depart from the more clear-cut and straightforward quantitative criteria under Article 3(2) when designating gatekeepers/CPS, in favour of the qualitative criteria under Article 3(1). It has done so both in accepting rebuttal arguments and not designating certain CPS (e.g. iMessage, Samsung Internet Browser, Outlook.com), and in designating iPad OS despite the quantitative thresholds not being met.

However, the Commission’s decision to reject ByteDance’s rebuttal arguments and designate TikTok demonstrates that, where the quantitative thresholds are met, the presumption of gatekeeper status can be difficult to overturn. Further, the reasons underlying that decision laid bare the differences between the DMA and the system of EU competition law from which it emerged. Whilst the DMA itself does not equate “gatekeeper” with “dominant”, the gap between the two concepts is becoming increasingly clear. Consequently, arguments rooted in competition law – including those relating to two-sided markets and ecosystems, highlighting the "challenger" status of a platform, or pointing to the competitive constraint imposed by larger incumbents – may well not prove persuasive.

The Commission has also signalled an intent to use its enforcement powers proactively and aggressively. It acted swiftly in opening non-compliance investigations less than three weeks after the initial gatekeepers’ compliance reports were submitted (and, strikingly, before all the compliance workshops had been concluded). Further, the stated grounds for opening those investigations (those in respect of Meta’s “pay or consent” model being a prime example) suggest that the Commission is prepared to adopt an outcomes-based approach, looking to the spirit as well as the letter of the regulation, when assessing gatekeepers’ compliance measures. (At the same time, the Commission having been compelled to immediately open non-compliance investigations could be said to reveal a limitation of the regime, namely the fact that gatekeepers’ compliance measures do not require pre-evaluation and approval before implementation.)

Commissioner Vestager has said it is “very likely there will be more cases”, and suggested that some companies were making “deliberate choices” not to comply. Third parties are likely to play a significant role in that enforcement process. The DMA itself enshrines the right of affected third parties to submit complaints to the Commission (or national competition authorities) and/or bring their own private enforcement proceedings. Commission officials have expressly encouraged stakeholders to make use of those rights, and the compliance workshops hosted by the Commission were a novel way of integrating external stakeholders into the process. A recently introduced whistleblower tool also encourages the submission of information on non-compliance by those with inside information. Competitors of gatekeepers and business users of CPS would therefore be well-advised to consider use of these avenues if they believe they are being adversely impacted by non-compliance with the DMA’s requirements.

1 See in particular our overview from November 2022 and update on the designation of gatekeepers from September 2023

Get in touch